现代社会主义者对于社会主义下的经济民主模式主要有两种类型的设想:一种是保留市场的市场社会主义,这种我之前在博客上有进行过介绍:经济民主模式介绍 ,这里就不再重复了;还有一种是完全废除市场的分布式民主计划经济,而这就是我今天要介绍的书籍内容和其作者Pat Devine的主张。

很多人一听到”计划经济“就炸毛,把计划经济等同于USSR和中国的中央计划经济(更准确的称呼是指令经济),其实并非如此,指令经济只是计划经济的其中一种,而且计划经济也根本不是社会主义的专利,事实上资本主义社会中已经出现过计划经济模式了。哦,不要惊讶,接下来我会介绍相关内容。

作者Pat Devine是英国政治经济学家, Manchester大学的教授,书籍下载链接:http://lib1.org/_ads/04FC9455A9641B8C99EBE0F19CBB2590

接下来就一起看看书籍内容吧。事先说明一点:Pat Devine是完全否定市场的(作者自己的说法是”保留市场机制,反对市场力量“,但其实际主张基本等同于完全不要市场),并且认为社会主义无法和市场兼容,而我并不赞同这点,但作为介绍者,我不会因此故意扭曲其言论,而是会如实介绍给所有人,让读者们自行判断。此外,这本书的写作对象也不是那些不了解社会主义的人,所以我建议初学者先根据我的指南搞清楚社会主义的基本概念主张历史流派,然后再来阅读这本书。

首先看看作者的总体介绍:

This is a book about transformation. It starts from two assumptions.

这是一本关于转型的书。 它从两个假设开始。

The first is that neither the capitalist countries of the West nor the statist countries of the East 1 represent acceptable ways of organizing society. A third way is needed, and to create it involves the conscious transformation of existing societies. The second assumption is that people create themselves by acting on the circumstances in which they find themselves. Depending on the internal and external resources available to them, people transform to a greater or lesser extent both their circumstances and themselves.

第一个假设是西方的资本主义国家和东方(1)的中央集权国家都不能代表可接受的组织社会的方式(这就是我为什么说这本书不是为不了解社会主义的人准备的,因为能接受这个假设的必然已经是社会主义者了)。 需要第三种方式,创造它涉及现有社会的有意识的转变。 第二个假设是人们通过根据在发现自己的环境中行动来创造自己。 根据人们可利用的内部和外部资源,人们或多或少地转变所在的环境和自己。

The third way set out in this book is a model of democratic planning based on negotiated coordination. It is democratic, which distinguishes it from the command planning of the statist countries. It is planning, which distinguishes it from the instability and lack of conscious social purpose characteristic of capitalist countries. It is based on negotiated coordination, which distinguishes it from market socialism, the only reasonably worked-out alternative model of a third way that has so far been proposed.

本书中提出的第三种方式是基于协商的协作的的民主计划模型。它是民主的,这与中央集权国家的指令计划不同。 它是计划的,将其与资本主义国家的不稳定和缺乏有意识的社会目标的特征区分开来。 它以基于协商的协作为基础,将其与市场社会主义区分开来,市场社会主义是迄今为止提出的唯一实践过的作为第三种方式的替代模式。

In the most advanced modern capitalist countries political democracy has been won but not economic democracy. The political democracy so far achieved is of unparalleled historical importance but it is incomplete. It is primarily passive representative democracy in which most people elect others to act for them. The extent of active participation in self-government is very limited and in many countries the centralization of political power is increasing. Economic power remains highly concentrated and economic democracy, although now on the agenda, is still fragmentary and for the future.

在最先进的现代资本主义国家,政治民主已被赢得,但经济民主没有被实现。迄今为止取得的政治民主具有无可比拟的历史重要性,但它是不完整的。它主要是被动的代议制民主,其中大多数人选举其他人为他们采取行动。积极参与自我治理的程度是非常有限的,而在许多国家政治权力的集中化正在增长。经济权力仍然保持高度集中,经济民主虽然现在已列入议程,但仍然是零碎的,也是未来的。

Modern capitalism is not laissez-faire capitalism. The role of the state has increased inexorably during the twentieth century, notwithstanding the rediscovery of economic liberalism in the 1980s. Part of this process has involved attempts at economic planning, primarily during the two world wars but also in the period since the Second World War.

现代资本主义不是自由放任资本主义。 尽管在1980s重新发现了经济自由主义,但在二十世纪,政府的作用不可避免地增加了。 这一过程的一部分涉及经济计划的尝试,主要是在两次世界大战期间以及第二次世界大战以来的时期。

However, planning has been limited, partial and largely unsuccessful. By the 1980s attempts at national economic planning had been effectively abandoned and macroeconomic management was in crisis. High levels of unemployment and inflation, persistent inequality, acute social divisions, environmental problems, the effects of unplanned technical change, international economic instability – all suggested a social system out of control.

但是,计划是有限的,部分的,并且很大程度上是不成功的。 到1980s,国家经济计划的尝试已被有效的放弃,宏观经济管理陷入危机。 高失业率和通货膨胀,持续的不平等,严重的社会分裂,环境问题,无计划的技术变革的影响,国际经济的不稳定性—这些都表明社会制度失控了。

The statist societies of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe have centrally planned economies. Planning has enabled the mobilization of their human and material resources for the priority objectives of developing their backward economies and modernizing their societies. It has also enabled them to achieve full employment, low levels of inflation, and a more equal distribution of income than exists in capitalist countries at the same level of development. However, both political and economic power are highly centralized and neither political nor economic democracy exists in these societies.

苏联和东欧的中央集权社会有中央计划的经济。 计划使他们能够动员人力和物力资源,实现发展落后经济和社会现代化的优先目标。 它还使他们能够实现充分就业,低通胀水平和比同等发展水平的资本主义国家更平等的收入分配。 然而,政治和经济权力都是高度集中的,在这些社会中既不存在政治民主也不存在经济民主。

As the level of economic and social development has increased, the statist societies have experienced endemic and periodically acute crisis. The absence of political democracy has resulted in a series of political crises, most dramatically in Poland in 1980. The combined absence of political and economic democracy, in a context of full employment and command planning, has resulted in lack of dynamism, economic inefficiency and labour indiscipline. Repeated attempts to deal with these systemic problems by introducing economic reform had come to very little by the mid-1980s, apart perhaps from in Hungary. The advent of Gorbachev in 1985 ushered in a new era in which for the first time in the Soviet Union the connection between economic performance and democracy has been officially recognized.

随着经济和社会发展水平的提高,中央集权社会经历了地方性和周期性的严重危机。 政治民主的缺乏导致了一系列政治危机,1980年在波兰发生的政治危机是最大的。在充分就业和指令计划的背景下,政治和经济民主的缺失导致缺乏活力,经济效率低下和缺乏劳动纪律。通过引入经济改革来反复尝试处理这些系统性问题在1980s中期几乎没有,除了匈牙利之外。 1985年戈尔巴乔夫的到来开启了一个新时代,苏联第一次正式认识到经济表现与民主之间的联系。

In both East and West overcentralization, bureaucracy and the exercise of arbitrary state or private power are now widely acknowledged to be major problems. The threat to personal freedom from the concentration of political and sometimes economic power in the state, the paternalism of nationalized industries and welfare state provision, the inefficiency of statist command planning, the power and lack of social accountability of large corporations, have between them led to a search for ways of decentralizing political power and economic decision-making.

在东方和西方的过度集中化中,官僚主义和政府或私人权力的任意行使现在被广泛认为是主要问题。个人自由受到了政治的集中化和政府的经济权力的威胁,国有化产业和福利国家提供中的家长式作风,中央集权指令计划的低效率,大公司的权力过大和缺乏社会责任感等, 这些导致了对分散政治权力和经济决策的方式的寻找。

Market socialism, in varying forms, has been increasingly advocated by reformers in the East and socialists in the West as the only wayforward, the only viable third way. At a theoretical level the work of Lange (1938),Brus (1972) and Nove (1983) has been especially influential. At the level of historical experience the Yugoslav system of worker self-managed enterprises, whose activities are in principle coordinated by the market mechanism, is unique. There is also the Hungarian new economic mechanism, far less of a break with the command system than might appear and qualitatively different from the Yugoslav system.

东方的改革者们和西方的社会主义者们越来越多地倡导各种形式的市场社会主义,将其当成唯一可行的第三条道路。 在理论层面上,Lange(1938),Brus(1972)和Nove(1983)的工作尤其具有影响力。 在历史经验方面,南斯拉夫的工人自我管理企业制度,其活动原则上由市场机制协调,是独一无二的。 还有匈牙利的新经济机制,与指令系统和与南斯拉夫系统相比可能出现的质量差别要小得多。

The strongest argument for market sociallsm is that it is the only realistic, or feasible (Nave 1983), alternative to capitalism and, more particularly, to statist command planning. Its advocates accept that Yugoslavia has experienced the sort of economic instability and crisis more usually associated with the capitalist West and that Hungary’s economic performance has not been noticeably better than that of other statist countries. However, the absence of political democracy means that neither country fully qualifies as an example of the sort of system recommended by market socialists. In any case, no one would expect market socialism, or indeed any system, to be perfect. The question is: is there a better alternative? Is there another third way?

市场社会主义的最强有力论据是,它是唯一现实的,或可行的(Nave 1983)对资本主义的替代,更具体地说,是对中央集权的指令计划的替代。 它的拥护者接受南斯拉夫经历了比资本主义西方更频繁的经济不稳定和危机,而匈牙利的经济表现并没有明显优于其他中央集权国家。然而,政治民主的缺乏意味着这两个国家都没有完全符合市场社会主义者主张的那种制度。无论如何,没有人会认为市场社会主义或任何制度都是完美的。 问题是:有更好的选择吗? 还有第三条道路吗?

This book is an attempt to show that there is, by developing a model of democratic planning based on negotiated coordination. In my view there are two fundamental problems with the model of market socialism which mean that it cannot constitute the economic part of a realistic vision of a self-governing society based on political and economic pluralism. The first is contingent. The case for planning is that it enables the conscious shaping of economic activity, in accordance with individually and collectively determined needs, and it overcomes the instability that is an endemic empirical characteristic of market-based economies. So far, neither historical experience nor the state of theory gives any reason to suppose that market-based economies can be managed or regulated effectively enough to achieve these objectives.

本书尝试通过制定基于协商的协作的民主计划模型来证明第三条道路是存在的。在我看来,市场社会主义模式存在两个基本问题,这导致它不能构成基于政治和经济多元化的自我治理的现实社会愿景的经济部分。第一个是偶然性。计划的情况是,它能够根据个人和集体的确定的需求有意识地塑造经济活动,并且克服了市场经济的地方性经验特征造成的不稳定性。 到目前为止,历史经验和理论状态都没有给出任何理由支持基于市场的经济能够得到有效管理或监管以实现这些目标的假设。

Second, the invisible hand, even if it could be steadied to avoid instability and guided to achieve broad social objectives, necessarily operates through an appeal to narrow individual or sectional self-interest and the coercion of market forces. It thus reinforces individualism and atomization and precludes conscious participation by people in the taking of key decisions that affect their lives. This, in turn, has far-reaching implications for motivation and the possibilities for linking the present and the future through transformatory activity and experience.

第二,看不见的手即使可以被稳定以避免不稳定并被引导以实现广泛的社会目标,也必然通过呼吁缩小个人或部门的自身利益以及对市场力量的强制来实现。因此,它加强了个人主义和原子化,并阻碍了人们有意识地参与影响他们生活的关键决策。 反过来,这对动机和通过转型活动和经验将现在和未来联系起来的可能性产生了深远的影响。

The fact that I reject market socialism as a model for the future does not mean that I necessarily regret the attempts currently being made to increase the role of the market in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China. In my view, as argued in chapter 5, these are not socialist societies but rather societies with a non-capitalist social formation constituting an alternative to capitalism as a means for creating the material and cultural preconditions for socialism. It may be that a greater role for the market will be part of the process of undermining the monolithic political power of the state in these countries and moving towards political democracy, undoubtedly the central challenge facing them.

我拒绝将市场社会主义作为未来模型的事实并不意味着我一定会对目前为增加苏联,东欧和中国市场的作用所做的努力而感到遗憾。在我看来,正如第5章所论述的那样,这些不是社会主义社会,而是具有非资本主义社会形态的社会,构成资本主义的替代,作为一种创造社会主义的物质和文化先决条件的手段。 市场的可能的更大作用将是破坏政府在这些国家中的整体政治权力并走向政治民主的过程的一部分,这无疑是他们面临的核心挑战。

以上来自1.1 Introduction,作者明确指出,基于协商的协作的民主计划经济是人民自我治理,自己决定自己的命运所必需的,同时作者也表现出了对市场机制的极度不信任,认为市场本身就是对民主的破坏。同时作者也明确说明了苏联和中国的指令经济模式既没有政治民主也没有经济民主,根本不是社会主义。

接下来看看作者支持民主计划经济的具体理由:

Within standard economic theory market failure is recognized as a reason for collective action in cases when atomized self-seeking individual action cannot achieve the objectives of the individuals involved, namely, when prisoners’ dilemma situations, externalities or public goods exist. In prisoners’ dilemma situations, atomized decision-making prevents decision-makers from taking account of interdependencies that affect the outcome. The result is an outcome that none of the decision-makers would have chosen had they been able to get together to reach an agreed decision. It has been suggested that such situations make sense of Rousseau’s notion of the general will, normally dismissed as a totalitarian concept by methodological individualists (Runciman and Sen 1965).

在标准经济理论中,市场失灵被认为是在原子化的自我追求的个人行为无法实现所涉及的个人目标的情况下而采取集体行动的原因,即当存在囚徒困境,外部性或公共物品时。在囚徒困境中,原子化的决策使决策者无法考虑所影响的结果的相互依赖性。结果是,如果他们能够聚在一起达成决定,那么决策者们都不会选择这样的结果。 有人认为,这种情况是卢梭关于公意的概念的体现,通常被方法论个人主义者贬低为极权主义概念(Runciman和Sen 1965)。(越来越大越来越疯狂的市场营销投入就是囚徒困境带来的恶果之一,结果是浪费了大量财富。)

Prisoners’ dilemma situations arise from the fact that in atomized decision-making people are by definition ignorant of the behaviour of others, yet to act effectively in their own narrow self-interest they need to know what the others are doing. In this they differ from situations in which externalities occur since externalities do not in principle arise from ignorance or uncertainty. Externalities exist because property rights are defined on too small a scale for the consequences of the use of property to be felt only by those who determine that use. They consist of costs or benefits that are not taken into account by narrowly self-interested decision-makers since some of the effects of using the property are borne by or benefit others. The extent and distribution of such external effects depend on the distribution of property rights. Externalities are the theoretical basis for the standard distinction between private and social costs and benefits.

囚徒困境源于这样一个事实,即在原子化的决策中,人们根本不了解别人的行为,然而为了在他们自己狭隘的自身利益中有效行动,他们需要知道其他人在做什么。在这方面,它们与外部性发生的情况不同,因为外部性原则上不是由无知或不确定性引起的。 存在外部性是因为产权的定义规模太小,只有确定使用的人才能感受到财产使用的后果。它们包括狭隘的自利决策者未考虑的成本或收益,因为使用财产的某些影响是由他人承担或使他人受益。这种外部影响的程度和分布取决于产权的分配。外部性是私人和社会成本与收益之间进行标准区分的理论基础。(最典型的外部性案例就是环境污染,私人独裁企业为了利润最大化,拒绝处理污染物,把环境成本扔给普通人,特别是穷人去承担。)

Finally, there is the case for the collective provision of public goods. These are goods and services with two characteristics: first, everyone is affected by them, whether or not they are prepared to pay for them or want them, that is, no one can be excluded from their effects; and, second, their use by one person does not diminish their availability for use by others. The classic examples are law and order and defence. However, the concept of public goods can be extended to embrace collective provision contributing to the general fabric and ethos of a society, ranging from the prevailing level of education and standard of public health to a sense of solidarity and community.

最后,集体提供公共产品的情况也是如此。 这些是具有两个特征的产品和服务:首先,每个人都受到它们的影响,无论他们是否准备为它们付钱或想要它们,也就是说,没有人可以被排除在它们的影响之外; 第二,一个人使用它们并不会减少别人使用时的可用性。经典的例子是法律和秩序以及防御。 然而,公共产品的概念可以扩展到包括对社会有帮助的一般构造和思想的集体供给,从普遍水平的教育和公共卫生标准到感觉到团结和社区。(人权也是一种公共产品,必须也只能由民主的公有机构,也就是政府来提供。)

National decisions are likely to include: the rates of growth and investment, and therefore the overall balance between investment and consumption; the allocation of investment for the major expansion of key existing industries and the creation of new industries; the distribution of investment between regions; energy and transport policy; policy towards pollution control, environmental protection and resource conservation; the balance between individual household consumption and collective social provision; the distribution of personal income and a corresponding incomes policy; the coverage and character of social provision, including education and training, recreation, housing, health, social services and social security; science and research policy, in particular the sort of innovation to be encouraged; and the priority to be given to the promotion of more human social relations.

国家决策可能包括:增长率和投资率,以及投资和消费之间的总体平衡; 为了重点扩大现有主要产业和创造新产业而进行的投资分配; 区域间的投资分配; 能源和运输政策; 污染控制,环境保护和资源保护政策; 个人家庭消费与集体社会供给之间的平衡; 个人收入的分配和相应的收入政策; 社会供应的范围和性质,包括教育和培训,娱乐,住房,健康,社会服务和社会保障; 科学和研究政策,特别是鼓励创新; 并优先考虑促进更多的人类社会关系。

Of course, most of these issues are not left to the spontaneous workings of the invisible hand in modern capitalism. They are decided by the interaction of state policies, decisions of the large corporations and the struggles of the labour movement and other organized interest groups. Within this interaction, however, the private sector is favourably placed to dominate the outcome because of what Lindblom has called ‘the privileged position of business’ (Lindblom 1977, ch. 13). This privilege arises from the need for governments to create an environment that will induce the private sector to perform satisfactorily. It is supplemented by the economic power of business which gives it preferential access to the decision-making institutions and processes of the state.

当然,大多数这些问题并不是由现代资本主义中看不见的手的自发运作所决定的。它们取决于政府政策的相互作用,大公司的决策以及劳工运动和其他有组织的利益集团的斗争。然而,在这种互动中,由于Lindblom称谓的“商业的特权地位”(Lindblom 1977,第13章),私有机构有利于处在主宰结果的位置上。这种特权源于政府需要创造一种环境以促使私有机构取得令人满意的成绩。它还得到了商业经济权力的补充,使其能够优先进入政府的决策机构和进程中。

If the private sector becomes too discontented with government policies there will be what may be called a capital strike or, in an international context, a flight of capital. For macroeconomic performance, the structure of resource allocation and the general direction of development of the economy to be determined democratically requires a fundamental redistribution of economic and political power. That is why socialists have historically sought the abolition of exploitation and private ownership and the abolition or democratization of the state. A redistribution of economic power is also a precondition for a more equal distribution of income, since investment would then no longer be motivated by the pursuit of unearned income accruing to private capital ownership.

如果私有机构对政府政策过于不满,那么可能会出现所谓的资本攻击,或者在国际范围内,会出现资本外逃。对于宏观经济表现而言,资源分配结构和经济发展总体方向的民主确定需要对经济和政治权力的根本的重新分配。 这就是为什么社会主义者历来寻求废除剥削和私有制以及废除国家或民主化国家。经济权力的再分配也是进行更平等的收入分配的先决条件,因为投资将不再受到追求私人资本所有权的未实现收入的驱动。

以上来自1. 4 The Case for Planning,作者描述了资本主义带来的恶果(囚徒困境,对外部性的忽视,公共服务的缺乏以及私有独裁资本对民主的威胁),而基于协商的协作民主计划经济会克服这些恶果。

接下来再来看看作者对民主计划经济模式的设想:

Although capitalist countries do not have planned economies there are elements of planning to be found in them from which we can learn. These elements, discussed in the next chapter, are concerned primarily with ways of modifying the operation of market forces and the consequences of uncoordinated decision-making. Economic planning, however, is normally associated with the statist countries. The rapid rate of economic development in the Soviet Union during the 1930s is evidence of the formidable ability of its centralized command planning system to mobilize and concentrate resources. The experience of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe until recently in maintaining full employment and avoiding inflation suggests the different order of control over an economy made possible by planning. Much can be learned from the experience of statist planning, which is discussed in chapter 3. Yet the absence of democracy, the human cost involved and the mounting problems now evident suggest that the lessons are as much negative as positive.

虽然资本主义国家没有计划经济,但我们可以从中学到计划的元素。下一章讨论的这些要素主要涉及改变市场力量运作的方式以及不协作决策的后果。然而,经济计划通常与中央集权国家有关。1930s苏联经济的快速发展证明了其集中的指令计划系统动员和集中资源的强大能力。直到最近苏联和东欧维持充分就业和避免通货膨胀的经验表明,通过计划可以实现对经济的不同秩序的控制。从第3章讨论的中央集权计划的经验中可以学到很多东西。然而,民主的缺乏,人的成本和现在越来越多的问题表明,这些教训中积极的和消极的一样多。

What is needed is a form of democratic planning combining centrally taken decisions where necessary with decentralized decision-making wherever possible. Market socialism, discussed in chapter 4, is widely held to be the only way in which this can be achieved. Regulated market socialism, its advocates claim, would dispense with capitalist social relations and thus enable market forces to be harnessed to planning. I believe, on the contrary, that the argument developed in the previous section establishes a strong prima facie case against the possibility of using the market mechanism as an instrument of planning.

我们需要的是一种民主计划形式,在必要时将必要的集中决策与分散决策相结合。 第4章讨论的市场社会主义被广泛认为是实现这一目标的唯一途径。 其支持者声称,受管制的市场社会主义将消灭资本主义的社会关系,从而使市场力量能够被用于计划。 相反,我认为,上一节中提出的论点确立了一个强有力的表面证据,就是反对将市场机制作为计划工具的可能性。

I wish to distinguish between market exchange, on the one hand, and market forces, or the invisible hand, or the anarchy of production, on the other. By these latter terms I mean a process whereby change occurs in the pattern of investment, in the structure of productive capacity, in the relative size of different industries, in the geographical distribution of economic activity, in the size and even the existence of individual production units, as a result of atomized decisions, independently taken, motivated solely by the individual decision-makers’ perceptions of their individual self-interest, not consciously coordinated by them in advance. It is to this process that I am referring when I argue against the use of market forces or the market mechanism as an instrument of economic planning. 9

我希望区分市场交换和市场力量,或看不见的手,或生产的无政府状态。在后面的术语中,我指的是一种进程,在这种进程中,投资模式,生产能力结构,不同行业的相对规模,经济活动的地理分布,个体生产的规模甚至存在都会发生变化。个体生产单位作为原子化决策的结果,独立地采取,仅由个体决策者对其个人自身利益的看法所驱动,而不是事先由他们一起有意识地协作。 当我反对使用市场力量或市场机制作为经济计划工具时,我指的是这个过程。9

No contemporary model of planning, whether statist, regulated market socialist or the model of negotiated coordination developed in Part IV, incorporates the direction of labour or the rationing or free distribution of all consumer goods. The continued existence of labour markets, in which people agree to participate in production in exchange for income, and of consumer markets, in which consumer goods and services are bought and sold, is not at issue. At issue between statist and regulated market socialist models is whether all decisions affecting the activities of production units are taken centrally and communicatedvertically downwards as instructions or whether some decisions are arrived at by horizontal interaction. At issue between regulated market socialist models and the model of negotiated coordination is whether horizontal interaction must necessarily involve market forces, the market mechanism.

没有现代的计划模式,无论是国家主义者,受监管的市场社会主义者还是第四部分制定的谈判协调模式,都包含了劳动力的方向或所有消费品的配给或自由分配。 劳动力市场的持续存在,其中人们同意参与生产以换取收入,以及消费者市场,其中购买和销售消费品和服务,这些都不是问题。 在中央集权和受监管的市场社会主义模型之间的问题在于,所有影响生产单位活动的决策是否作为指示进行集中和传播,或者是否通过横向互动得出某些决策。 受监管的市场社会主义模式与基于协商的协作模型之间的问题在于,横向互动是否必然涉及市场力量,即市场机制。

At the moment, in all economies, most transactions between enterprises are based on an established pattern of horizontal relationships which are only reassessed when they cease to satisfy the requirements of those involved. 10 These relationships are between producers and users and in market economies constitute what I have called above market exchange. Change in the established pattern resulting from reassessment typically involves negotiation. The model of negotiated coordination is a qualitative development of this existing reality. In it, such horizontal relationships and reassessments continue to be the basis of transactions concerned with current production, that is, most transactions. However, the crucial difference by comparison with market economies is that negotiation is extended to embrace relationships between enterprises in the same branch of production when changes in capacity are at issue. Thus, while market exchange exists market forces do not.

目前,在所有经济体中,企业之间的大多数交易都是基于既定的横向关系模式,只有当它们不再满足相关人员的要求时才会被重新评估。 10这些关系是生产者和使用者之间的关系,市场经济构成了我称为市场交换的存在。重新评估产生的既定模式的变化通常涉及协商。基于协商的协作模式是对现有现实的性质上的发展。其中,这种横向关系和重新评估仍然是与当前生产有关的交易的基础,也就是说,绝大多数交易。然而,与市场经济相比的关键差异在于,当出现产能变化问题时,谈判扩展到包括同一生产部门中的企业之间的关系。因此,虽然市场交换存在,但市场力量却不存在。

This crucial difference enables decisions about changes in the size of production units and branches of production, about investment or contraction, to be coordinated in advance. It enables decentralizationof routine, day-to-day decisions to be combined with coordinated decision-making when significant interdependence is present. Thus, when decisions potentially affecting the future of individual workplaces and communities are being taken, those potentially affected can participate consciously in taking them. In this way, negotiated coordination, unlike command planning instruction and market force coercion, creates the possibility for people consciously to transform their perceptions, values and motivation by confronting their own interests with those of others and seeking a resolution. As is elaborated in Part IV, the process of negotiated coordination can be generalized to incorporate all interests affected by major decisions and to cover all major decisions affecting people’s lives. The interests participating in negotiation can be constituted narrowly or broadly, involving more or less (de )centralization, according to the issue. 11

这种至关重要的差异使得能够提前对关于生产单位和生产部门的规模变化,投资或收缩的决定进行协作。它使分散的日常决策与当存在显着的相互依赖时的协作决策相结合。因此,当正在考虑可能影响个人工作场所和社区未来的决策时,那些可能受影响的人可以有意识地参与其中。通过这种方式,与指令计划指示和市场力量强制不同的是,基于协商的协作为人们创造了通过将自己的利益与他人的利益一起考虑并寻求解决方案而有意识地改变其观念,价值观和动机的可能性。正如第四部分所阐述的那样,谈判协调的过程可以概括为包含受重大决定影响的所有利益,并覆盖影响人们生活的所有重大决策。根据这个问题,参与谈判的利益可以狭义或广泛地构成,或多或少地(集中)集中化。 11

It will, I hope, be clear that the model of negotiated coordination is not based on the assumption of perfect knowledge or optimality. In relation to neoclassical theory’s ‘myopic concentration on problems of marginal adjustment’, Dobb has referred to the ‘Perfectibility Fallacy’ (Dobb 1970b, p. 121). In Ellman’s view, the waste and inefficiency of statist planning arise because it is based on the false assumption of ‘a perfect knowledge, deterministic world, in which unique perfect plans can be drawn up for the present and the future’ (Ellman 1979, p. 73). More generally, Lindblom has distinguished between two models, with different assumptions about the nature of social reality: Model 1, based on the possibility of perfectibility and the scientific discovery of correct solutions in the interests of all – the paternalist model; and Model 2, based on the permanence of fallibility and on preference-guided choice through a process of social interaction – the pluralist model (Lindblom 1977, ch. 19).

我希望,它将清楚地表明,基于协商的协作模式不是基于完美知识或最优性的假设。关于新古典主义理论的“近视的集中于边际调整问题”,Dobb 提到了“完美主义谬误”(Dobb 1970b,p.121)。在Ellman看来,中央集权计划的浪费和低效率的出现是因为它基于一个关于”完美的知识,确定的世界,其中可以为现在和未来制定独特的完美计划”的错误假设(Ellman 1979,p .73)。更一般地说,Lindblom区分了两种模型,针对社会现实的本质有不同的假设:模型1,基于完美性的可能性和为科学发现所有人的利益提供正确的解决方案—家长式模型;和模型2,基于易犯错误的永久性和基于对社会互动过程的偏好引导选择—多元模型(Lindblom 1977,ch.19)。

The process of negotiated coordination in my model has similarities with the ‘social processes or interactions that substitute for conclusive analysis’ in Lindblom’s Model 1(Lindblom1977, p. 253). However, in the economic sphere, although not unaware of the problems associated with private property and atomized decision-making, Lindblom espouses the market mechanism as the way of organizing preference-guided, pluralist social interaction. He sometimes also gives the impression of underestimating the role that knowledge and reason can and should play in the process of self-determining, self-governing democratic decisio-making. My model of negotiated coordination is not based on perfectibility, whether of knowledge or solutions, but it is based on a belief in reason and in the possibility of transformation and progress.

我的模型中基于协商的协作的进程与Lindblom模型1中的“社会过程或相互作用取代结论性分析”相似(Lindblom1977,第253页)。 然而,在经济领域,虽然并未意识到与私有财产和原子化决策相关的问题,但Lindblom支持市场机制作为组织偏好引导的多元社会互动的方式。 他有时也给人的印象是低估了知识和理性可以也应该在自我决定的和自我治理的民主决策过程中发挥作用。 我的谈判协调模式不是基于完美性,无论是知识还是解决方案,而是基于对理性的信念以及转型和进步的可能性。

第二部分是分析资本主义国家和中央集权国家的计划经济案例,例如英国二战时期的计划经济,凯恩斯主义的宏观经济计划,英国和法国二战后的对工业发展的指示,日本的工业计划和保护主义模式,以及苏联和东欧的指令经济模式,还有匈牙利和南斯拉夫的市场社会主义尝试。限于篇幅我这里就不再具体介绍了,诸位自己去阅读吧。

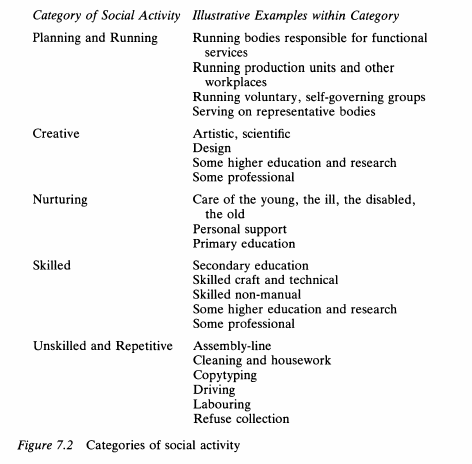

第三部分介绍了作者打算用民主计划经济模式实现的目标,有社会化生产,政治民主(包括直接的参与式民主),经济民主,最终消灭劳动的社会分工,让每个人都能平等的做自己想做的工作,而作者最终的设想是这样的:

这张图里的英语很简单,所以我就不翻译了,诸位自己看吧。

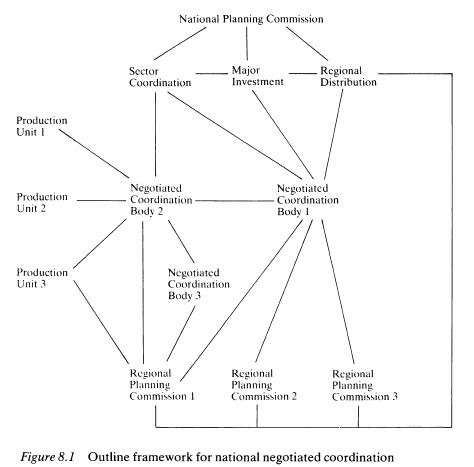

第四部分具体讲述了作者的民主计划经济方案:

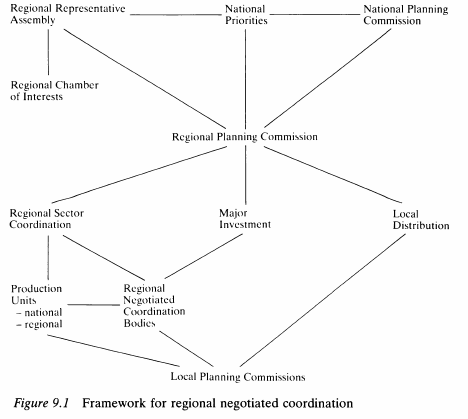

这是国家层面的方案,国家计划委员会下属有三个机构:部门协调机构,主要投资机构,地方分配机构。部门协调机构负责和地方计划委员会以及生产单元们(生产单元由工人们民主控制)进行基于协商的协作,协调生产单元们之间的问题;而主要投资机构则是负责民主的协商投资;地方分配机构则是和地方协商,对国家控制的资源进行民主分配。所有这些机构的作用都是协助人民民主的进行决策,任何被影响到的人民都有权参与协商决策,当然它们本身也是被民选议会控制的(甚至本地可以实现直接的参与式民主控制。)

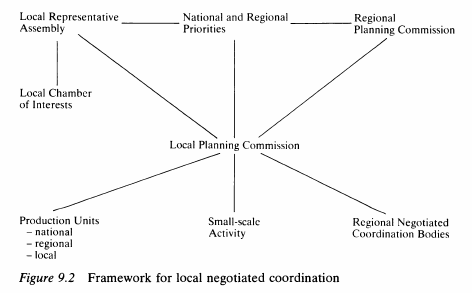

这是地方(省一级)层面的方案,地方计划委员会一方面是国家计划委员会以及地方代表议会的下属,地方代表议会同时也下属地方利益机构。另一方面也和国家计划委员会一样下属三个机构:地方部门协调机构,主要投资机构,本地分配机构,这三个机构的功能也和国家层面的三个对应机构一样,只是范围局限在地方。

这是本地(城市,小镇,乡村)层面的方案,本地计划委员会一边是国家和地方的计划委员会和本地代表议会的下属(本地代表议会也下属本地利益机构),和地方进行民主协作,另一边则是和生产单元以及小规模活动进行直接的民主协商。

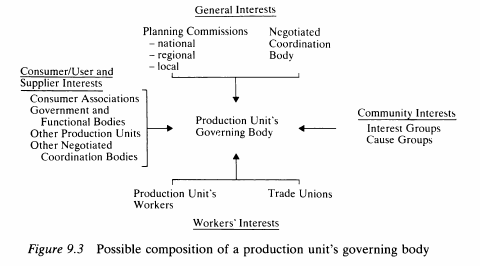

这是生产单元层面的方案,工人们通过工会或者直接与消费者们以及其他生产单元或协作机构或社区民主的进行协商,然后根据协商结果制定生产计划,再进行生产。

最后作者进行了总结:

Thus, the central requirement for advance to a self-governing society of equal subjects is movement towards more equal access to the material and psychological resources necessary for self-development. Abolition of the social division of labour is the precondition for ending the oldest forms of oppression and inequality, between men and women and between mental and manual labour. It is also a precondition for achieving global ecological balance, since the end of subalternity and alienation will enable people to transform their unconscious need for compensatory consumption into a conscious need for emancipatory activity. If capitalism and statism have today in their different ways created the objective and subjective possibilities for advance to socialism, communism and self-government, it is up to us to decide whether to act on those possibilities, whether to draw on the internal and external resources available to us to transform both our circumstances and ourselves.

因此,推进平等主体自我治理社会的核心要求是更加平等地获得自我发展所需的物质和心理资源。 废除社会分工是结束存在于男女之间以及脑力和体力劳动之间最古老的压迫和不平等形式的先决条件。 这也是实现全球生态平衡的先决条件,因为等级压迫和异化的结束将使人们能够将他们对补偿性消费的无意识需求转变为对解放活动的有意识的需求。 如果资本主义和中央集权今天以不同的方式创造了推进社会主义,共产主义和自我治理的客观和主观可能性,那么我们有责任决定是否采取行动,是否利用内部和外部资源。以改变我们的外部环境和我们自己。

If we decide to do so, we have to find ways of going beyond reliance on the operation of impersonal market forces for the coordination of our economic activity. The model of democratic planning through negotiated coordination outlined in Part IV is an attempt to show that this is possible without recourse to administrative command planning. It is an attempt to demonstrate that there is a third way that is both realistic and yet has a transformatory dynamic. The only other third way that has been proposed, regulated market socialism, is neither realistic nor transformatory. It is based on an internally inconsistent political economy in which people undertake economic activity on thebasis of narrow self-interest yet regulate themselves by non-narrowly self-interested political action in the social interest. Democratic planning through negotiated coordination, by contrast, is a model that offers us the possibility of taking responsibility for our lives and in so doing transforming ourselves.

如果我们决定这么做,我们必须找到超越依赖非个人市场力量运作来协调我们的经济活动的方法。第四部分概述的通过基于协商的协作进行民主计划的模式尝试表明这可以不借助行政命令计划实现。它试图证明第三条道路既现实又具有变革动力。唯一被实践过的第三种方式,即管制市场的社会主义,既不现实也不革命。它建立在内部不一致的政治经济基础之上,人们在狭隘的自身利益的基础上开展经济活动,并通过社会利益中的非狭隘自利的政治行动来约束自己。相反,通过基于协商的协作进行的民主计划是一种模式,它使我们有可能对我们的生活负责,从而改变我们自己。

Movement towards democratic planning and a self-governing society requires political action informed by a hegemonic political strategy. Without the development of autonomous, self-governing groups in civil society, struggling to assert their interests in relation to the state and the economy, there can be no progress. Without such groups finding the way to transform their existing subaltern, sectional, consciousness into hegemonic, overall, consciousness, there can be no challenge to the dominant position of the ruling hegemonic group. Transformatory political action has to be informed by a credible vision of a better society. One of the factors inhibiting such action has been the crisis of the traditional socialist vision, not least the loss of confidence in the possibility of combining freedom and democracy with planning. I hope that the model of democratic planning through negotiated coordination will contribute to thinking about how, particularly in relation to the economy, optimism about the possibility of a better society can be combined with realism about how people are and what we can become, what together we can make of ourselves.

实现民主计划和自我治理的社会的运动需要以占主导的政治策略为依据的政治行动。如果没有公民社会中的自治的,自我治理的团体的发展,努力维护这些人自己与政权和与经济相关的利益,就没有进步。如果没有这样的团体找到将他们现有的下层的,部分的,无意识的转变为主导的,整体的,有意识的方法,那么就不会有任何对统治霸权集团的主导地位的挑战。转型政治行动必须了解更美好社会的可信愿景。阻碍这种行动的因素之一是传统社会主义愿景的危机,尤其是丧失对通过计划将自由与民主相结合的可能性的信心。我希望通过协商协作的民主计划模式将有助于思考如何做,特别是在经济方面,对更好的社会的可能性的乐观可以与关于人是怎样的和我们可以成为什么的现实主义相结合,我们可以在一起塑造我们自己。

作者的设想比较理想化,相比市场社会主义的主张,作者的主张离现实更遥远(如果说市场社会主义主张大政府,那么Pat Devine主张的就是超级政府),但作为一种思路还是不错的。毕竟我们不能由着那些霸占生产资料和资本的独裁者们胡作非为,对吧?