https://twitter.com/sanzaosandra/status/997023618361012224

什么是民主社会主义?民主社会主义就是推翻一切压迫,建立无阶级的自由人的联合体。为初学者准备的教程:https://democraticsocialism.noblogs.org/post/2018/07/04/socialism-study-guide/

https://twitter.com/sanzaosandra/status/997023618361012224

(写在前面:任何科学成果,不,任何知识,都是建立在前人的劳动的基础之上的,既然前人选择了分享劳动果实,那么今人又有什么资格垄断知识呢?任何形式的知识垄断,都是对其他人的剥削!)

在俄羅斯高等經濟學院,四個人、一隻貓、還有一台由13塊硬盤組成的服務器,擠在一間狹小的學生宿舍裏。這台服務器的主人,是一名來自哈薩克斯坦的女孩,高等經濟學院在讀研究生、進程員亞歷珊德拉•厄巴科揚(Alexandra Elbakyan),而這台藏在宿舍裏的簡陋服務器,是一個名叫Sci-Hub的網站主機,上面有6400萬篇供全世界所有人免費下載的學術論文。

2015年6月平常的一天,厄巴科揚打開郵箱,一封郵件跳了出來。“你被起訴了!”

起訴她的,是全球最大的學術出版商,旗下有2500家權威期刊的愛思唯爾(Elsevier)。很顯然,厄巴科揚的網站侵犯了他們的著作權。然而厄巴科揚只是聳聳肩。她人在莫斯科,法院在美國,不能拿她怎麼樣。她只是一個小研究生、互聯網上千萬個不知名的“黑客”(如果她算的話)之一。即使她的Sci-Hub和這場官司,已經處於整個學術圈的爭論中心,也極少有人知道她姓甚名誰。

如果你還不知道Sci-Hub的話,你可以問問你身邊做研究的小夥伴,他們或多或少有着在Sci-Hub上搜一篇在犄角旮旯發表過的論文的經驗。這是世界上最大的盜版學術論文網站。

為什麼會有“盜版學術論文”呢?這跟盜版音樂和盜版圖書又有什麼區別呢?

隨便在愛思唯爾旗下的在線期刊打開一篇學術論文,你可以看到,讀到一篇論文的花費,在十幾到幾十美元不等;訂閲這些期刊的費用更是高到不可思議——平均需要4000多美元。想要越過擋在研究者和期刊之間的這堵“付費牆”(paywall),對於高校和研究機構之外的人來説,幾乎不可能。哪怕對於高校的圖書館和數據庫而言,每年需要支付的費用也十分巨大,且逐年上漲;一所大學要投入50至200萬美元不等,連哈佛大學也曾抱怨。發展中國家的高校或者一些小型研究機構常常無法負擔高額的數據庫費用;而想要深入學術研究的研究者,卻往往面對這堵付費牆發愁。一個研究常常需要參考幾十、上百篇文獻,而來自著名期刊的論文,往往是最重要的。

即使是高校,也會因為資金問題選擇性地購買數據庫。圖片來源:Pixabay

即使是高校,也會因為資金問題選擇性地購買數據庫。圖片來源:Pixabay

那麼這些高昂的訂閲費,是否惠及到了寫論文的著作人呢?至少在經濟上並沒有。著作人是拿不到稿費的,大多數情況下還要付版面費。這些高額的訂閲費用,通常用於支撐整個學術出版業界的運作——編輯、同行評審、校稿,有的雜誌社還僱有專門的市場營銷、公關、新聞發佈人員,以及社交媒體運營等。

在科學研究發展的早期,學術期刊是公益性質的存在,通常也非常簡陋、缺乏完善的管理。但是二戰之後,隨着科學技術行業的爆炸性發展,期刊走向了商業化運營,面向各種新領域的期刊如雨後春筍,大出版集團也把控住了期刊話語權。關鍵是,在頂級期刊上發表文章,幾乎是學術成果被承認、學術機構間正式交流成果的唯一方式,而商人們也清楚,這個需求是無止境的,被政府和非政府學術基金支持的市場,也將會日益龐大。全球每年有一半以上發表的論文,都被六大學術出版集團把控(Reed-Elsevier,Wiley-Blackwell,Springer,Taylor & Francis,American Chemical Society,Sage Publishing)。

厄巴科揚第一次遭遇付費牆,是2009年的事。彼時的她還在哈薩克斯坦阿拉木圖做自己的本科研究論文。付費牆讓她沮喪的同時,她也意識到,這並不是一件“正常”的事情。

業餘時候的厄巴科揚喜歡研讀一些神經科學方面的東西。她將科學研究的成果,比作“全人類的智能網絡”。如果神經網絡之間互相連接能夠讓信息傳遞更高效、能夠誕生更為先進的智能,那麼人類的智能成果也不應該被付費牆所阻擋。她認為,歷史上偉大的科學成就,都得益於最偉大思想之間的交流和碰撞,以及“站在巨人肩上”往下看;而科學想要生存,必須要科學家向全世界“喊出”他們的研究結果才行。

美國科學社會學家羅伯特•默頓(Robert Merton)曾經提出,科學應該是普遍主義的、利益無涉的,貫徹有組織的懷疑主義(organized skeptism),以及共產主義的。理科出身的厄巴科揚在2016年方才接觸了默頓的理論,於她而言是一種頓悟,更是一種不謀而合。“西方的資本主義出版集團”,無疑是橫貫在科學和真理之前的一座大山。

學術成果是否該標價,這一點在學術界也頗有爭議,相當一部分的學者贊同免費。理論上,各國大學由政府使用納税人的撥款資助學術工作者的研究,至少本國納税人有權知曉並查閲學術研究成果,而不是由大的出版公司收買。但是也不得不承認,商業化的運作,支撐了學術出版業的繁榮,以及科學傳播事業的進行。

近年來,由研究者們主導的運動,例如開放出版運動(Open Access),得到了越來越多人的支持,其中包括開放出版的期刊PLOS(科學公共圖書館),以及鼓勵研究者們以個人身份上傳的Arxiv(電子預印本文庫)。各類學術社交媒體,例如researchgate和Academia等,也由研究者個人提供非正式版本的論文下載。目前,有大約28%的學術論文通過開放出版的方式供分享。開放出版的期刊通常由非盈利機構提供資金資助,有的也會向研究者收取更多的版面費來維生。2013年,美國政府執行了一項規定,由聯邦基金資助的學術成果,必須要以某種方式出現在開放出版領域(比如上傳到 Arxiv等)。

因為論文獲利最大的是出版商。圖片來源:Pixabay

因為論文獲利最大的是出版商。圖片來源:Pixabay

秉持開放出版的學術界,和坐享巨大利益的出版集團之間,保持着一種微妙的平衡。出版集團對研究者的“分享”有諸多限制(名曰“負責任的分享”,還專門有一個機構來推行他們認為合適的分享準則),例如不可分享最終修訂的正式版本,必須經過一定時間之後才能分享,等等。而在背後,則是強大的遊説集團,阻止政府制定有利於開放出版的政策,還迫使Researchgate撤下了700萬篇“不符合分享規定的論文”。

厄巴科揚是開放出版運動的支持者。她在本科畢業之後,曾經試圖在“俄羅斯硅谷”、斯科爾科沃創新中心(Skolkovo Innovation Center)創建一個俄國版的、類似於PLOS的出版項目,但是並沒有成功。心灰意冷的她申請了俄羅斯高等經濟學院唸了一個科學和宗教史相關的碩士學位,但並沒有放棄編程。她覺得,戰勝這堵“付費牆”、達成“絕對無阻礙的分享”的唯一辦法,就是“盜版”了。

侵犯他人著作權的“盜版”,顯然是違法的。然而因特網誕生以來的匿名、公平和免費原則,又一直和用版權盈利這件事本身相牴觸,諸如Creative Common等運動,都是秉承互聯網精神的“反知識產權”行為。而所謂“黑客”,則繞開規則,用“違法”的激進手段達成這一目標。真正的黑客們大多誕生於資本主義的技術繁榮之下,卻從骨子裏反資本主義,Sci-Hub和厄巴科揚“科學共產主義”的無私追求,可以説是黑客的一種詮釋。

於是,Sci-Hub充滿爭議又多舛的命途,從莫斯科的一間宿舍裏開始了。

厄巴科揚從小學的時候就開始接觸編程了,做一個準黑客進程對於她來説並不是什麼難事。最初,她編寫了一個腳本,用 MIT 的學生賬號自動登錄各大期刊網站,然後下載論文。一開始她也沒有全部公開這個腳本,而是在俄羅斯的一個學術交流論壇上分享自己下到的論文。

後來,她把這個搬運的人力活兒,變成了人人可以“一鍵使用”的Sci-Hub。Sci-Hub正式誕生於2011年,是她的一個業餘項目。人們可以在Sci-Hub搜索論文,然後通過進程腳本、使用某個大學的登錄賬號,跳轉到論文的下載界面。這是通過大學的服務器完成的,如果一個服務器不行,用户可以換另一個大學的。但所有的論文只能被“借閲”,一定時間之後就無法打開了。

後來,另外一個知名“學術盜版”網站LibGen(一個存儲未授權學術書籍的網站)找到了厄巴科揚,讓她可以把下載下來的論文放到LibGen的服務器上,這樣就可以更容易地多次使用搜索結果。然而LibGen遭受了一次變故,服務器數據丟失,厄巴科揚轉而求助眾籌,為Sci-Hub購得了一個服務器。那時候,Sci-Hub上已經有了2100萬篇論文。她在網站上掛上了自己的Paypal,討得一些資金,然後轉而支付一些酬勞給提供大學賬號密碼的學生們——具體數目有多少,不得而知。

高校學生提供的幫助是Sci-Hub能夠壯大的原因之一。圖片來源:Pixabay

高校學生提供的幫助是Sci-Hub能夠壯大的原因之一。圖片來源:Pixabay

這樣大量的數據,精明的出版商不可能不察覺。2013年,愛思唯爾發現了這件直接危及他們利益的情況。愛思唯爾發函給Paypal,厄巴科揚的賬號被關停。但這僅僅是漫長鬥爭的開端。遭遇了這次小小打擊之後的厄巴科揚並沒有特別沮喪。她一邊開始自己的研究生學習,一邊開始重寫代碼,並把整個數據庫做了好幾個備份。新的腳本能自動檢查各大高校網絡代理的運行情況,並在大學賬號中切換,而用户可以直接下載到論文,不必一個個大學切換。接着,她把捐助渠道改成了比特幣——比特幣在之後幾年的瘋漲,倒是為她帶來了一些意外之財。

愛思唯爾隨後發現了來自一些大學賬號的非正常訪問記錄。他們聯繫大學,把這些賬號或者代理賬號封掉,或者直接從自己的網站上阻止某些IP登錄。但是厄巴科揚手上的大學賬號特別多,根本封不完。當然,她自己也非常小心地控制着訪問數,在必要的時候“關掉中國和美國等大宗訪問量來源地”,或者只開放給“前蘇聯各國”。

為了徹底繞開學校這一關,厄巴科揚修改了腳本,不是從學校賬號直接獲取論文,而是獲取文章的密鑰。然後再用密鑰,從數據庫直接下載論文。這個策略沿用到了現在——只要你有論文的DOI(Digital object identifier,數字對象標識符,發表的期刊論文所獨有的一個數字編碼,在論文網站上都有顯示),輸入Sci-Hub的搜索框,論文就可以在瀏覽器中以pdf格式顯示或下載下來。

這讓各大出版商從技術上幾乎無計可施。

但這場戰爭畢竟實力懸殊。出版商擅長的並不是技術,而是強大的法務集團和遊説集團,面對侵權者可以在法庭要求互聯網供應商掐斷盜版網站線路,讓搜索引擎不顯示搜索結果(儘管谷歌對此並不理會),或者讓DNS無法解析域名。而面對“合法”的對手,愛思唯爾的遊説集團出入政府國會,阻礙學術分享的法案落地——他們曾於2005年讓美國衞生研究所公開出版的政策難產,更於之後試圖“攔截”3次此類議案。儘管他們因此遭到一萬七千名研究者的聯名抵制,讓他們態度有所軟化,但這根本對他們造不成實質性威脅。他們不僅是能“殺死”盜版網站,Researchgate這樣的合法分享網站,也得對他們言聽計從。

果然,毫無懸念地,2015年,愛思唯爾在美國起訴了Sci-Hub和厄巴科揚並勝訴,賠償額為1500萬美元;美國化學協會(American Chemistry Society)跟進,同樣也勝訴,賠償額為480萬美元。Sci-Hub先後失去了 .ac, .cc,.io 等域名。

有的人把厄巴科揚比作女版的阿倫•斯瓦茨(Aaron Swartz),後者是Creative Common的發起者、著名網站Reddit的創始人。斯瓦茨因為使用自己MIT的賬號自動、大量地下載學術數據庫Jstor上的論文用作公開分享而被起訴,隨後不堪壓力而自殺。現在唯一能保護厄巴科揚的,就是她身處俄羅斯這個事實。她偶爾會擔心自己出境、進入歐洲或者美國的時候會不會被逮捕。但只要她不離開俄羅斯,美國法院的判決,從現實上無法在她這樣一個身處別國的別國公民身上強制執行,民事案件也更不存在引渡一説。俄羅斯薄弱的版權保護也為她提供了方便。

“我不會賠付的,我根本沒有那麼多錢。”她聲稱網站每個月只能收到區區數千的捐贈,外加在2017年價值大約26萬美元的比特幣。Sci-Hub還存在着,擁有自己的 IP 地址和推特賬號,告訴用户怎麼訪問網站。

她在衞報的一個採訪中説,“學術應該屬於所有科學家,而不是出版商”,並引用了聯合國人權宣言的第27條,“……(擁有)分享科學進步及其產生福利(的權益)”。

雖然她的目標,是完全沒有邊界的、世界範圍的信息共享,但是現狀卻是,作為一個哈薩克斯坦公民、俄羅斯居民,厄巴科揚的自我認同更偏向所謂的“東方”,而對西方的社會和民主抱有疑慮。她坦誠,自己“學術共產主義”的思想來自前蘇聯,她想為更多第三世界、沒有頂級研究條件的人提供方便——比如,來自伊朗的學者,幾乎無法訪問美國的任何期刊網站。她爭辯説,發達國家也有並不富有的學者,而資本主義加劇了這一切的惡化。甚至是在俄羅斯國內,她也和所謂的“自由主義學者”們有過沖突,甚至一氣之下拔了Sci-Hub的服務器好幾天。

不過,Sci-Hub有四分之一的下載來自世界上34個最發達的國家,這也成為了Sci-Hub被指摘的一個點。《科學》雜誌(Science)網站上發佈的一篇統計顯示,許多下載來自美國東部的精英大學。而下載的理由很簡單:方便。只需要一個DOI,不用搞賬號、登錄等繁瑣進程,也不用考慮學校究竟有沒有購買某一個數據庫。

厄巴科揚是一個孤獨的人。在西方,從事開放期刊的人對Sci-Hub一直持謹慎態度。哈佛大學開放期刊項目負責人彼得•蘇博(Peter Suber)不推薦用户“使用非法方式”獲取資源,他也擔心,盜版會對整個開放期刊事業帶來不好的名聲。“其實,現在你只要發郵件給研究者要文獻,他們都會給的。”她的名字很少被英文世界提起,雖然Sci-Hub本身處於爭議旋渦之中。

厄巴科揚,正孤獨地走在這條“共享”道路上。圖片來源:Pixabay

厄巴科揚,正孤獨地走在這條“共享”道路上。圖片來源:Pixabay

拋開這些爭議,Sci-Hub依然以自己的方式運轉着。2017年7月的一項研究表明,Sci-Hub 覆蓋了全世界有標識碼的在線論文的68.9%。根據谷歌趨勢(Google Trend)的統計,每一次主要的法律判決和公開爭議過後,Sci-Hub的訪問量都會得到提升。2017年,光是中國訪客就貢獻了2400萬次下載;有24次下載甚至來自南極洲。

然而更加堅挺的,依然是學術出版巨頭。愛思唯爾的母公司勵訊集團(RELX Group)的市值估價為350億美元;旗下的科學出版部門的利潤率為令人咋舌的39%(作為參考,蘋果公司去年12月份的利潤率為22%)。羅伯特•馬克斯韋爾(Robert Maxwell),西方學術出版商業化的第一個巨頭,在1988年的時候曾這樣預測:未來會有幾個最強大的出版公司控制整個學術出版業,然後在電子出版的年代不用承擔印刷成本,賺“純利潤”。看起來,他似乎是一語成讖了。

作者注:厄巴科揚在英文世界的資料非常稀缺,本文關於厄巴科揚的內容,大部分源於《The Verge》在2018年2月份對厄巴科揚的一次俄語採訪,以及一篇長篇報道[1]。隨後厄巴科揚在她自己的博客裏用很長的篇幅[2-4]對這篇報道做了解釋和部分反駁。本文對兩方的説法均進行了採納。

本文不推薦用非法的手段獲取內容。對於學術期刊的商業化運行、開放期刊運動和“學術盜版”,作者憾無法於本文有限的篇幅中一一深入探討,歡迎各方的討論和觀點,若有疏漏或片面之處請不吝賜教。(編輯:Ent,錦衣Reload)

題圖來源:Pixabay

https://hk.saowen.com/a/0f2675cede6ce35258a96b15594a23bd2ed99f4d606b2934046afa26283e9626

很多人都听说过“经济基础决定上层建筑”这句话,中共说,这是马克思说的,然后他们也就跟着这么认为了。实际上,如果去马克思的理论中查找这句话,会发现根本没有。对,你可以慢慢翻阅马克思的理论,你是找不到这句话的。

当然,有人会说,就算没有原话,但马克思也有这种思想。呵呵,那就让我们看看,马克思的原始表述是怎样的吧:人们在自己生活的社会生产中发生一定的、必然的、不以他们的意志为转移的关系,即同他们的物质生产力的一定发展阶段相适合的生产关系。这些生产关系的总和构成社会的经济结构,即有法律的和政治的上层建筑竖立其上并有一定的社会意识形式与之相适应的现实基础。物质生活的生产方式制约着整个社会生活、政治生活和精神生活的过程。不是人们的意识决定人们的存在,相反,是人们的社会存在决定人们的意识。

来源:https://www.marxists.org/chinese/marx/06.htm

“这些生产关系的总和构成社会的经济结构,即有法律的和政治的上层建筑竖立其上并有一定的社会意识形式与之相适应的现实基础。”硬要说马克思的哪个表述能扯得上关系,也就只有这句话了。但这句话说的是什么?说的是生产关系会影响上层建筑,对吧?

这一表述本身并没有问题。原始时代的氏族公有制,对应的就是狩猎采集生产关系;西欧封建制,对应的是定居农业为主的生产关系;现代右翼独裁或强市场弱民主制度,对应的是工业为主的资本主义生产关系。从历史和现实来看,生产关系和上层建筑(也就是政治制度)的确存在着紧密的关联。当然,这一关联并非严格对应,例如古希腊人的民主制,例如资本主义也有自由资本主义和国家资本主义的区别,但生产关系会对上层建筑产生很大影响,是可以肯定的。当然,反过来上层建筑也会影响生产关系,例如苏联和中国就是在建立起极权独裁制度之后才实行中央计划经济的。

那么生产关系是不是经济基础?问题就在这里:生产关系和经济基础根本不是一回事!举个例子,现代世界上几乎所有国家都被资本主义全球化卷入资本主义制度中了,也就是资本主义的生产关系,但中共说的经济基础是什么东西?是GDP,对吧?中共所谓的“中国还不够发达”的依据就是人均GDP,没错吧?那么请问,无论GDP是多是少,这能改变生产关系本身吗?富的资本主义国家是资本主义,穷的资本主义国家就不是资本主义了?真是可笑,生产关系和GDP之类的经济数据根本就毫无关联,想当年大清帝国的GDP还是世界第一呢,生产关系(小农经济)还不是落后于当时的西欧(工业为主)?

当然,马克思的这一表述也不是毫无问题。马克思过度重视生产关系的影响(当然生产关系会造成很大影响),轻视政治制度和社会文化等其他方面,这是其理论的缺陷之一。但这一缺陷,已经被后来的社会主义者们修正了(考茨基强调社会主义只能在民主的基础上建立,葛兰西提出文化霸权理论),而中共故意把生产关系偷换为“经济基础”(实际上是经济数据),目的不过是为了以“经济不够发达”为由拒绝人民的民主诉求而已。

1,全球福利国家体系是社会党国际在2008年雅典第23届代表大会中提出的概念。全球福利国家概念结合了市场竞争与充分就业和基于公共社会保障体系的社会一体化。其要素基于人权和能战胜腐败及其他政治犯罪行为的民主问责下的领导者。 北欧各国从一战开始建立福利国家,又在二战后逐步发展,这是一条可以推广到全球的模范道路。因此全球范围内都可以实行北欧福利国家模式。

2,21世纪第一个10年的金融和就业危机造成了全球性冲击,导致了持续时间较长的严重的国际经济不景气。世界也许正在迎接对经济认知的转变。

3,我们需要采取有效措施。危机的严重性意味着政治上的被动会导致更多的失业。靠继续等待是没用的。首要的是解决失业,恢复经济增长需要国际合作。故我们呼吁各国和全球重视。

4,金融危机已经给出了世界两大意识形态的答案。市场并非可自动调节的机体,政府从来不能通过放弃秩序和干预来恢复经济稳定。这两大因素显而易见,新自由主义作为一个经济意识形态走到了崩溃的边沿,经济危机无情地动摇了其理论基础。世界见证了一个历史极限,从美国和英国新自由主义政策开始至今30多年以后,也就是在他们建立了这种意识形态和无可挑战的市场信仰之后,其崩溃波及到了全世界。新自由主义政策也已经将其消极冲击扩展到了福利国家,现在这些福利国家处于被消灭的危险。

5,面对这个全球时代,需要全球社会民主主义勾画出解决危机的对策:建立全球福利国家模式。因此北欧福利国家模式可以为我们提供灵感。北欧经验在这次危机中为我们展示了免费的社会保障,稳定和平等的优越性。北欧经验显示在制定保持经济活力的政策,福利导向体制和充分民主的自由政权之间没有冲突。相反,它证明福利和社会公正是有利的,而且是可持续长期增长的先决条件。

6,北欧福利国家模式的价值可以为现在世界发展的持续辩论和质疑提供有力的回答。在未来的不确定和谋求变革中,政治价值观非常重要。当世界社会变革的方向被决定时,我们关注的重点就不仅是短期经济效益,而是长远发展。这就是为什么最基本的社会价值如此重要,和北欧福利国家模式的价值讨论可以为我们提供指导方针的原因。就全球方案中北欧福利国家模式的保障和进一步发展而言,它同时也是体现和发展社会民主主义基本价值观的关键。

7,北欧国家的社会民主党人和工会运动是今日北欧福利国家模式具有全球影响的建筑师们。

8,北欧福利国家模式的内容包括: 强有力的公共部门 公平的税收管理体制 有效的社会制度 就业保险 劳动力市场有强大的工会运动和集体协议做后盾 高就业率 普及每一个人的教育培训 保健和教育体系的普及,主要是公众监督下公共体系在养老金和收入保障上比低弱社会保障国家更加普及和广泛。 劳动力市场以性别平等基础上雇主和工薪族之间更公平的权力平衡为特点,这一特点是通过劳动力市场的谈判与合作来体现的。 北欧福利国家模式合理的金融保障在万一失业和失业可能延续时能在公民之间保持比全世界绝大多数国家更小的社会差别。

9,北欧模式培育了良好的可行性,为未来的危机提供了先进经验。北欧福利国家模式建立在以下价值观上:以团结互助取代个人主义化,以变革中的安全取代单个的排外主义,以保护工薪阶级来取代社会动荡。这些价值观也是解决金融和失业危机的基础。它是社会民主主义者和工会运动保障新工作和进步的最高目标。而且也避免了不平等增加,公民边缘化和侵害工薪阶级权利等倾向。

10,我们的价值观体现在现今与将来的具体政策上可以浓缩为三个关键概念:充分就业,福利和社会公正。这些概念有效地说明了包括21世纪当代和将来的社会模式。旧的观念实际上作为近年来的政治发展被赋予了新的定义。这符合隐藏在北欧政治争论后面的基本哲学,以期保障公民权和福利,让人民能以合理的方式肩并肩地生活在一起,同时也可保证不同国家内人口的增长和可持续发展。

11,这一模式背后增长起来的有关信息和基本价值的意识及其既有设计是朝政治学习和将在别的国家里产生积极效果迈出的第一步。 我们的主要挑战是在社会保障,社会包容性,机会平等和公平的高税收功能贯彻之间的相互联系。 在很多国家,收税是一个简单明了的问题。社会党国际将首要关注世界各地的辩论,如何说服大家相信从公共财政里得到社会保障是对所有公民有益的。

12,北欧福利国家模式的实践产生了强烈的争论,为支持其他国家里这种模式的改变,并得到鼓舞,强调某些模式发展中的关键因素显得非常重要: 人民对变革的反应该是安全感。所以,安全基础上的变革是不可或缺的因素。 北欧福利国家模式是在诸如社会公正,团结互助和充分就业等价值观基础上得到发展。这些价值观并不与经济活力和可持续发展相矛盾。 这些基本价值观透过经济危机证明了不论在过去还是在将来发生类似危机和挑战的时候,都给北欧国家打下了坚实的根基。 北欧福利国家是在五个小国中发展起来的。五国之间的地区合作促进了这个模式。社会党国际将就如何在其他国家和地区中推行全球福利国家体系的成功经验开始进行辩论。

13,北欧福利国家模式已能培育一个在紧要关头发挥作用的社会组织,并能使这些北欧国家进行有效配合。这个社会组织的主要特点是: 强有力的财政。它不仅是一个为小型开放经济减少弱点的问题,还是通过低通胀和高薪增长使经济良好运行的基础。 巨大的公共部门,以保健和教育培训得到更多公共控制和覆盖全体人员为特征。 自由贸易的支持者。自由贸易从来不容否定。现在贸易保护主义在全球范围内增长,却非解决办法。公平贸易是未来高增长的必要条件。 大规模的退休金,面向更多人的收入保障和社会保障。 因此,虽然总税收水平要比其他国家高,却是以收入均衡化为目的的。 社会桥梁—保护失业工人的政策。有三种类型的社会桥梁:终身学习,调节保险和再就业。通过巩固第一道社会桥梁,即便在调节过程中有阵痛,也能创造出一个灵活与有活力的社会。 经济上性别领域的冲击。设计政策帮助双职父母角色中的男人和女人。高质量的育儿中心和分享双亲离开系统。该系统提供高男女平等和高就业率。 绿色领域里环保与友善生产的推行是创造可持续社会和增长动力的重要手段。 与其他力量处于均衡的劳动力市场,尤其是比美国和英国等盎格鲁-撒克逊国家有更多的性别平等和通过谈判与合作所施加的影响。

14,劳动力市场的高工会化率说明北欧福利国家的重要优越性。它表明北欧地区的基本因素是以谈判与合作为特点的,而不是通过竞争和市场力量。

15,北欧国家在过去10年里胜利走过来了,主要是用高税收建立起来的巨大的福利财政部门。危机甚至使得保持北欧福利国家模式的必要性更为强烈。福利制度的趋势并非是在向下衰落,反而是在向上发展。

16,北欧福利国家模式需要不断的发展,以维护人民的安全保障与活力。但却没有改变模式的必要—因为这个模式本身就是为社会保障而建立起来的。

17,北欧经验告诉我们那些断言高增长和公平分配不可兼顾的人是错误的。恰好相反,北欧经验告诉我们经济增长和社会公正之间并不冲突。

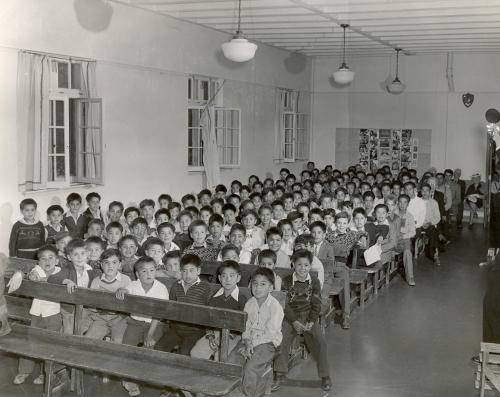

The forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families.

The forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families was part of the policy of Assimilation. Assimilation was based on the assumption of black inferiority and white superiority, which proposed that Indigenous people should be allowed to “die out” through a process of natural elimination, or, where possible, should be assimilated into the white community.[1]

Children taken from their parents as part of the Stolen Generation were taught to reject their Indigenous heritage, and forced to adopt white culture. Their names were often changed, and they were forbidden to speak their traditional languages. Some children were adopted by white families, and many were placed in institutions where abuse and neglect were common.[2]

Assimilation policies focused on children, who were considered more adaptable to white society than Indigenous adults. “Half-caste” children (a term now considered derogatory for people of Aboriginal and white parentage), were particularly vulnerable to removal, because authorities thought these children could be assimilated more easily into the white community due to their lighter skin colour.[3]

Assimilation, including child removal policies, failed its aim of improving the lives of Indigenous Australians by absorbing them into white society. This was primarily because white society refused to accept Indigenous people as equals, regardless of their efforts to live like white people.

When Ruth was 4 years old, she was separated from her mother on Cherbourng mission in Queensland. Ruth was 6 months old when she first arrived at Cherbourg. Times were tough; it was during the Depression, and Ruth’s mother had gone to Cherbourg seeking help for her ageing parents.

But once she arrived at the mission, Ruth’s mum was prevented from leaving. What was intended as a temporary visit became years of separation and control. “People would say it was for your own good, but my own good was to stay with my mum,” says Ruth.

At first Ruth was allowed to stay with her mum in the women’s dormitory. But eventually every child was removed to a separate dormitory. Ruth was 4 when she was taken from her Mum. “Once you were taken from your parents, you had no more connection with them,” she explains.

For a short time, Ruth still saw her Mum from a distance. But when Ruth was 5, her mother was sent away from Cherbourg and forced to leave her daughter behind.

The forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families had a profound impact that is still felt today.

In 1995, the Australian government launched an inquiry into the policy of forced child removal. The report was delivered to Parliament on the 26th May 1997. It estimated that between 10 per cent and 33 per cent of all Indigenous children were separated from their families between 1910-1970.

The report, Bringing Them Home, acknowledged the social values and standards of the time, but concluded that the policies of child removal breached fundamental human rights. The Keating government commissioned the inquiry into the Stolen Generations, but the Howard government received the report. Howard’s government was skeptical of the report’s findings, and largely ignored its recommendations.

What would you do if one day the police turned up to your home and took your children away simply because of the colour of your skin? How would you feel knowing you had no way of getting your children back and no higher authority to appeal to?

Imagine if one day you were at home with your parents and government officials came and took you away to live with strangers, and told you that you had to learn to live, eat, speak and dress differently than you were used to. How might that experience continue to affect you throughout your life?

Almost every Indigenous family has been affected by the forcible removal of one or more children across generations. Many people, families and communities are still coming to terms with the trauma that this has caused.

https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/australian-history/stolen-generations

The case for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) has rapidly become part of mainstream political debate. The Labour Party is actively considering the policy, in the US it was revealed Hillary Clinton almost included it as a manifesto pledge. Trials have recently begun across the world, including close to home in Scotland.

1,全民基本收入(UBI)的案例迅速成为主流政治辩论的一部分。 工党正在积极考虑这项政策,在美国,Hillary Clinton几乎将其列为宣言承诺。 最近世界各地开始进行试验,包括靠近家乡的苏格兰。

The policy is again in the news as the Finnish government chose not to fund an extension to their two-year basic income trial. This led to much speculation as to what this means for the policy, leading many to argue that a basic income had fallen flat. In reality, the government simply chose not to fund an extension to what was always intended as a time limited policy experiment. But this provides a useful chance for reflection on the idea of Universal Basic Income, its aims and the debate that surrounds it.

2,该政策再次出现在新闻中时,芬兰政府选择不资助延长他们的两年基本收入试验。 这引发了很多猜测,认为这对政策意味着什么,导致很多人认为基本收入已经失败。 事实上,政府只是选择不资助一个已经被设计为有时间限制的试验。 但是,这为思考普遍基本收入这一想法,它的目标以及围绕它展开的辩论提供了一个有用的机会。

The idea of Universal Basic Income, or Citizens Income, is superficially quite simple. A monthly payment made to every adult and/or child in the population, of equal value and with no conditions attached. No need to search for or be in work, no means testing, just a condition of citizenship.

3,全民基本收入或公民收入这个想法在表面上很简单。 每位成年人和/或儿童每月得到一笔钱,价值相等,没有附加条件。 不需要正在找工作或在工作,也不需要测试,只是公民权利的一部分。

For its proponents, UBI has several benefits. It would remove bureaucracy, and therefore cost, from the system through eliminating means testing, and protects workers in an increasingly insecure labour market. This latter point is particularly important in an age where many are concerned about the impact that automation and AI might have on our working lives, and the resultant power balances between capital and labour.

4,对于其支持者来说,UBI有几个优点。 它将通过测试消除手段来消除系统中的官僚作风,从而消除系统成本,并且在日益不安全的劳动力市场中保护工人。 后一点在许多人担心自动化和AI可能对我们的工作生活产生的影响以及由此产生的资本与劳动力之间的权力平衡的时代显得特别重要。

These benefits, and a perceived coalition of support from both left and right, have led many to view UBI as a potentially revolutionary policy which could bring about positive change to a welfare state battered by years of austerity and ideologically driven reforms.

5,这些好处,以及来自左翼和右翼两方的联合支持已经使许多人认为UBI是一项潜在的革命性政策,可以为受到多年紧缩和意识形态驱动的改革的打击的福利国家带来积极变化。

However, the superficial simplicity of a Universal Basic Income belies a multiplicity of versions, and raises several questions. At what level should a UBI be paid? How does it factor in children? How will it support those with disabilities or who are out of work? Will it sit alongside or replace existing social security arrangements? And most importantly, what are the economic arrangements which govern how a UBI would be paid for?

6,然而,全民基本收入的表面简单特性掩盖了多种版本,并提出了几个问题。 UBI应该在怎样的级别上支付? 它如何影响儿童? 它将如何支持那些残疾人或失业的人? 它会单独存在还是替代现有的社会保障安排? 最重要的是,关于如何支付UBI的经济安排是什么?

In reality, those who advocate Universal Basic Income have varied motivations for doing so, and there are also multiple versions of what a UBI could look like in practice. For instance, there is a drastic rift between those for whom UBI is about transforming the economy and those for whom it is about papering over its cracks. This acknowledgement is often lacking from the UBI debate, but should be of primary interest.

7,事实上,那些主张全民基本收入的人有不同的动机,而且在实践中也有多种版本的UBI。 例如,在认为UBI是转变经济的那些人中间与在认为UBI是那些为了抹平社会裂缝的人之间存在着巨大的裂痕。 在关于UBI的辩论中通常缺乏这种认知,但这应该是主要的议题。

Those who seek a radical departure from capitalism see UBI as part of a radical platform to move away from a world in which work is central to our lives, identities and economies. In their book Inventing the Future, Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek argue that UBI is a fundamental part of delivering a new economy in which citizens have much greater freedom over when and if they work.

8,那些试图彻底抛弃资本主义的人将UBI视为一个激进平台的一部分,用以摆脱一个以工作在我们的生活,身份和经济中占中心地位的世界。 在他们的书“发明未来”中,Alex Williams和Nick Srnicek认为UBI是提供新经济的基础部分,在那里公民们在工作时间和是否工作方面拥有更大的自由。

To do this, Williams and Srnicek acknowledge that UBI “must provide a sufficient amount of income to live on” so that people can refuse employment, thereby freeing them to engage in more meaningful labour, whether paid or unpaid. This is often picked on to claim that a UBI would simply be unaffordable. There is truth in this. While Williams and Srnickek have not proposed a specific payment level, modelling conducted by IPPR shows that were a UBI paid at a high enough level to meet the Minimum Income Standard (a measure of what the public think people need for an acceptable minimum standard of living), it would cost around £1.7 trillion a year – equivalent to almost all of the UK’s GDP in 2016.

9,为了做到这些,Williams和Srnicek认为UBI“必须提供足够的收入来维持生活”,以便人们可以拒绝就业,从而把他们解放出来,使他们能够从事更有意义的劳动,无论是带薪还是无偿。 这常常导致有人声称UBI简直无法承受。 这是有道理的。 虽然Williams和Srnickek没有提出具体的支付水平,IPPR进行的模拟表明,当UBI的支付水平足以满足最低收入标准(衡量公众认为人们需要达到可接受的最低生活标准的程度 )时,每年需要1.7万亿英镑左右的费用 – 几乎等同于2016年英国所有的GDP。

What this shows is that for UBI to be a viable proposition at these levels, there would need to be a fundamental transformation in the ownership of the economy. Williams and Srnicek acknowledge this, arguing that UBI will only work in combination with large scale and collectively owned automation, a reduction in the working week and a shift in social attitudes around the value of the ‘work ethic’.

10,这表明,对于UBI而言,在这些层面上可行的主张将需要对经济所有权进行根本性转变。 Williams和Srnicek承认这一点,认为UBI只能与大规模和集体所有的自动化相结合,工作周的减少,以及围绕“职业道德”价值观的社会态度的转变。

It is this level of transformation which sets the ‘post-workists’ against many other proponents of the policy. Those who argue for a basic income from a post-work platform have little in common with the tech entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley who are funding trials of UBI in the US. For this group, the appeal of a basic income lies in its ability to offset the impacts of automation and AI, whilst their creators still accrue the benefits. Here, rather than using technology to facilitate a radical platform, UBI is a capitulation to the rise of inequality in the age of the robot and AI.

11,正是这种转变级别使得“后工作主义者”反对许多其他这一政策的支持者。 那些主张从工作后平台获得基本收入的人与在美国资助UBI试验的硅谷科技企业家几乎没有共同之处。 对于这个群体来说,基本收入的吸引力在于它能够抵消自动化和人工智能的影响,同时他们的创造者仍然获得收益。 在这里,UBI不是利用技术来建立一个激进的平台,而是对在机器人和人工智能时代上升的不平等的投降。

This critique has been central to the argument forwarded by left wing opponents to UBI who argue that it is an individualistic policy that accepts a status quo in which capital exploits labour. These criticisms recognise that as an indiscriminate policy UBI is blind to structural inequalities in a way the labour market isn’t. As Anna Cootes notes, UBI fails “to tackle the underlying causes of poverty, unemployment and inequality”.

12,这种批判是左翼反对者向UBI提出的论点的核心,他们认为这是一种接受资本剥削劳工的现状的个人主义政策。 这些批评认识到作为一项不进行任何区分的政策,UBI对于结构性不平等是盲目的,并不像劳动力市场那样。 正如Anna Cootes指出的,UBI未能“解决贫困,失业和不平等的根本原因”。

That there are radically different visions for Universal Basic Income is somewhat lost in a policy debate, which often presents UBI as a catch all policy which can offer both cost-effective efficiency and radical emancipation for those on low incomes. Worryingly this tension, and the myth of a coalition of support between left and right which underpins it, might see policymakers sleep walking into a position that suits very few.

13,对于全民基本收入存在着极端不同的看法在政策辩论中有所丢失,这种辩论常常将UBI视为所有能够为低收入者提供具有成本效益的效率和激进解放的政策的一项措施。 令人担忧的是,这种紧张局势和支撑它的左翼和右翼的联合支持的神话可能会让政策制定者们走入一个适合很少人的位置。

In Scotland for example, the Green Party has proposed a model of UBI which could get close to being fiscally neutral. This would see much of the existing welfare system replaced by a payment of £5,200 per year for adults and £2,600 for children, alongside significant reform the tax system. In this scenario, personal allowances would be removed and combined tax and NI rates increased for all.

14,例如,在苏格兰,绿党提出了一个UBI模型,该模型可能接近于财务中性。这将看到许多现有的福利制度被替换成向成年人支付5,200英镑,向儿童支付2,600英镑,同时还有重大的税制改革。 在这种情况下,个人津贴将被撤销,复合税率和国民税率都会增加。

Citing security in the labour market as a key reason for the policy proposal, this model has been welcomed by proponents of UBI. However, at £400 a month for adults while also removing almost all the welfare state, it is unlikely to buy much economic freedom for those on low incomes or insecure and exploitative employment contracts. In reality some would see their incomes drop. For instance, in Scotland lone parents would see their monthly earnings fall by around £300 a month.

15,确保劳动力市场的安全性是作为政策提案的一个关键理由,这种模式受到了UBI的支持者的欢迎。 然而,对于成年人而言每月400英镑同时也移除了几乎所有福利国家,但对于低收入者或签订了不安全和剥削的就业合同的人来说,购买很多经济自由的可能性不大。 事实上有些人会看到他们的收入下降了。 例如,在苏格兰,单身父母每月的收入会下降300英镑左右。

What’s more, a model of UBI paid at this level would also have notable impacts on rates of relative poverty. Were this model introduced in the UK as a whole, it would also raise relative child poverty by 17%, placing a further 750,000 children into households who earn below 60% of the median income. This is because while it would raise the incomes of those earning the least, it would also raise incomes for all but the highest income decile, lifting the poverty line higher.

16,更重要的是,这种在这一水平上的UBI支付模式也会对相对贫困率产生显著影响。 如果这个模型在整个英国引入,它还会使儿童的相对贫困率增加17%,并将75万名儿童增加到收入水平低于中等收入的60%的家庭中。这是因为虽然这会提高收入最低的人的收入,但除了最高收入等级之外,它还会提高其他所有人的收入,从而抬高了贫困线。

Research commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has similarly found that UBI schemes increase relative poverty for working age adults, children and pensioners. The introduction of a UBI, according to their modelling, could see the number of children in poverty rise by up to 60%.

17,Joseph Rowntree基金会委托进行的研究同样发现UBI计划增加了在工作年龄的成年人,儿童和养老金领取者的相对贫困程度。 根据他们的模型,UBI的引入会造成贫困儿童的人数上升60%。

Increasing the incomes of those at the bottom of the distribution is imperative. This is demonstrated clearly by the rise of food banks deprivation and income crisis in the UK since 2010, which is a direct result of government policy choices. However, using a UBI to achieve this, at the expense of say increases or reforms to Universal Credit and a more generous and less conditional unemployment benefit, comes at the cost of addressing, and in fact exacerbating, relative poverty.

18,增加分配底层人员的收入势在必行。 自2010年以来,英国食品银行的匮乏和收入危机的抬头就清楚地表明了这一点,这是政府政策选择造成的直接结果。 然而,使用UBI来实现这一目标,其代价是增加或改革普遍债务,以及更慷慨和更少条件限制的失业福利,这是以造成相对贫困为代价的,并且事实上加剧了相对贫困。

Action on relative poverty is important, and inequality is not cost free. As Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson show in their book ‘The Spirit Level’, countries with higher rates of inequality perform worse against a range of social outcomes – physical health, mental health, drug abuse, education, imprisonment, obesity, social mobility, trust and community life.

19,对相对贫困进行行动很重要,不平等不是免费的。 正如Kate Pickett和Richard Wilkinson在他们的书“精神等级”中所表明的那样,不平等程度较高的国家对一系列社会结果表现更差 – 身体健康,心理健康,药物滥用,教育,监禁,肥胖,社会流动,信任和社区生活。

The pursuit of a fiscally neutral UBI has led to a series of proposals which, if implemented, would do little to raise the material circumstance of those in poverty nor provide sufficient additional power in the labour market. In light of this, can it be really said that such proposals meaningfully fit with a progressive, radical vision for the welfare state?

20,追求财政中立的UBI已经产生了一系列提案,如果得到落实,这些提案几乎无助于提高贫困人口的物质状况,也不会为劳动力市场提供足够的额外动力。鉴于此,这样的建议是否真的可以说符合福利国家渐进式的激进愿景?

The need to act in delivering a better vision for the welfare state is clear. In 2016, 22% per cent of adults and 30% of children were living in poverty. By 2019/20 the number of children in poverty could increase by 500,000. This is driven by political choices, the consequence of welfare reform and austerity. As such, it is welcome that as a society we are discussing more ambitious plans for the collectivisation of income and wealth and how it can be best deployed to support the needs of all in society.

21,明确表达出为福利国家提供更好愿景的必要性是很清晰的。在2016年,22%的成年人和30%的儿童生活在贫困中。 到2019/20年,贫困儿童人数可能增加到50万。 这是由政治选择推动的,福利改革和紧缩造成的后果。因此,值得欢迎的是,作为一个社会,我们正在讨论更加雄心勃勃的关于集体化收入和财富的计划,以及如何最好地分配以支持社会上的所有人的需求。

However, unless we are to engage in a radical economic transformation which drastically increases common ownership of economy, it is unlikely that Universal Basic Income on its own will do more than lock us into our current predicament. In the meantime, we need to look for equally radical policies which make a much more material difference to the lives of those on low incomes and who suffer from structural inequalities. Proponents of UBI need to go big or go home.

22,然而,除非我们要进行一场彻底的经济转型,这会大大增加集体的经济所有权,否则基本收入本身不可能做除了把我们锁在目前的困境中的之外的事。与此同时,我们需要寻求同样激进的政策,这些政策对低收入者和遭受结构性不平等问题的人的生活产生更大的物质影响。 UBI的支持者们需要做大,或回家。

华盛顿 — 美国证券交易委员会目前正在对投资银行摩根大通香港办公室雇用中国高官子女一事进行调查 。观察人士指出,美国大公司雇佣中国高干子女的目的是打开通向中国市场的方便之门,然而这样做有可能违反了美国的反海外腐败法。

这次美国证券交易委员会 (The Securities and Exchange Commission) 对摩根大通 (JPMorgan) 的调查主要涉及两名中国政界高层的子女。《纽约时报》的报道指出,摩根大通香港办公室在2007年和2010年分别雇用了原铁道部副总工程师张曙光的女儿张曦曦和中国光大集团(China Everbright Group) 董事长唐双宁的儿子唐晓宁。随后,中国中铁股份有限公司(China Railway Group) 和中国光大集团相继成为摩根大通的客户。

华尔街银行为发展在中国的业务而雇用中国政界高层子女的做法并非个案。例如,前国家主席江泽民的孙子江志成曾任职高盛公司 (Goldman Sachs)、前国务院总理温家宝的女儿温如春曾在瑞士信贷 (Credit Suisse) 银行工作、前总理朱镕基的儿子朱云来在1995至1997年间曾任职安达信 (Arthur Anderson) 和瑞士信贷。前人大委员长吴邦国的女婿冯绍东也曾在2006年帮助美林证券 (Merrill Lynch) 赢得了中国工商银行上市的合同,融资额为220亿美元。

《中国即将崩溃》(The Coming Collapse of China) 一书的作者章家敦 (Gordon Chang) 律师说,这种用工作来换取合同的利益交易被称为“猎捕大象”(Elephant Hunting)。

章家敦说:“这个现象自从中国开放以来就有了。八十年代我在香港居住的时候这个现象就存在了。重要的国家官员就像‘大象’,他们的孩子通常在国外的商学院接受很好的教育。所以如果华尔街银行要得到大额合同的话,他们必然要去接近这些高官的子女。这就是所谓的‘猎捕大象’。”

章家敦认为,这在中国非常普遍,因为中国的体制不能提供一个开放的、公平竞争的市场,所以做生意在很大程度上要靠“关系”。

他说,在张曦曦和唐晓宁加入摩根大通后,中铁和光大成为摩根大通的客户,这决非巧合。 章家敦说:“我相信如果摩根大通没有雇用这两名高官子女,它是不会赢得那些合同的。虽然这并不证明其中有违反了《反海外腐败法》的腐败行为,但是至少引发推测,是不是其中有些问题。”

美国联邦法律《反海外腐败法》 (Foreign Corrupt Practices Act) 在1977年签署,由美国司法部和美国证券交易委员会执行。南伊利诺伊大学法学院 (Southern Illinois University School of Law) 助理教授 (Assistant Professor) 迈克尔•凯勒 (Michael Koehler) 说:“《反海外腐败法》是一项禁止美国公司以及在美国进行证券交易的外国公司向外国官员贿赂,以达到赢得生意的目的。”

凯勒是反腐败法案方面的专家,他说除了直接的贿赂,间接的贿赂例如通过第三方代理、顾问、总代理、合资伙伴等也是被禁止的。

根据美国证券交易委员会公布的数据统计,自2010年以来,证交会调查的案件中至少有七件涉及贿赂中国官员。国际金融公司摩根士丹利 (Morgan Stanley) 的前高管加思•彼得森 (Garth R. Peterson) 在2012年就因为涉嫌贪污及贿赂一名中国官员而受到证交会和司法部的调查。其它受到指控的公司有IBM、 辉瑞制药有限公司 (Pfizer)、Biomet、洛克威尔自动化公司 (Rockwell Automation) 等。

这些案例中比较常见的是用现金、礼品、旅行、娱乐等方式来行贿,而通过雇用中国官员家属来获得业务的案子数量比较少。凯勒说,上一次类似案件是在2010年,美国司法部指控戴姆勒•克莱斯勒公司 (Daimler Chrysler) 违反了《反海外腐败法》。根据司法部公布的文件,其中一项指控是该公司在2002年,获得中国石化(Sinopec) 业务之后,给中国石化一名中国政府官员夫人支付了5万7千欧元的“佣金”。虽然有合同,但实质上这位夫人并没有为这家公司工作。

凯勒说,雇用高官家属本身并不一定违法。 他说:“这件事情本身并没有错,但是要调查这其中是否有贪腐的动机。例如,被雇用的那个人是否胜任这项职位,支付给那个人的工资是否符合市场的价位,等等。”

《纽约时报》的报道指出,美国证交会在今年5月要求摩根大通提交有关资料,包括在职工资、雇用纪录、离职后与摩根大通之间的通信纪录、以及相关合同及协议等。

章家敦认为,虽然摩根大通提交了很多材料,但是证交会要找到摩根大通违反《反海外腐败法》的证据有一定难度。他说:“我认为证交会是在查找摩根大通投行和中国高官之间贪腐交易的协议,如果摩根大通雇用他们的子女,摩根大通将会得到项目或好处。实际上我认为要找到这样的证据是非常困难的,因为很少有明确的协议,通常是双方之间的共识,所以这当中的过程是比较微秒的。”

除了在华尔街公司任职外,很多中国政界高层的子女也开始在中国建立风险投资基金、私募基金等。例如,前国家总理温家宝的儿子温云松在2009年参与创立了新天域资本公司 (New Horizon Capital),并为双汇集团对美国史密斯菲尔德食品公司 (Smithfield Foods) 的收购融资。2012年美国梦工厂 (DreamWorks SKG) 宣布在上海成立合资公司东方梦工厂(Oriental DreamWorks),而投资方之一的上海联合投资有限公司 (Shanghai Alliance Investment Ltd.) 的法人代表江绵恒正是前国家主席江泽民的儿子。同年,美国证交会也开始对包括梦工厂在内的至少5家好莱坞电影公司进行调查,切入点是这些公司是否为进入中国市场而有违反《反海外腐败法》的行贿行为。

在美国政府加强对华尔街在中国雇用太子党调查的同时,中国政府也发起了一场反腐倡廉运动。章家敦说:“习近平的反腐倡廉运动是有一定的成效,但这只是暂时的,因为它不涉及问题的根源,而腐败的根源是不负责任的政治体制以及政府过多干预经济活动。虽然也有很多贪官进了监狱,但是他们并不是由独立的检察官在一个独立的法院系统中受判的。往往是当权者的政治敌人被送入了监狱,所以这并不是真正的反腐败。这其实是政治斗争。”

章家敦认为这次的调查会令很多华尔街公司更加小心,重新考虑在中国的投资风险,以及如何通过合法的途径做生意。

华盛顿 — 纽约时报曝光美国证券交易委员会(SEC)正在调查摩根大通(JP Morgan Chase)是否通过雇用中国高官子女以获得在中国丰厚业务的消息多少让人感到有些吃惊,因为国际大型金融机构通过雇用中国高官后代以获得在华业务的做法已经盛行了至少二十多年。

*华尔街青睐官二代由来已久*

“在过去将近二十年,(它)都是一个很突出的现象,就是西方国家(公司)利用中国高官、领导人子女和关系拓展在中国的市场,”纽约城市大学的夏明说,“这里边从胡耀邦、赵紫阳的子女或者是亲属,到以后朱镕基、江泽民他们的亲属,到今天披露出来的中国的高官,包括王岐山、周小川,还有戴相龙等等。他们都是跟西方国家有非常密切的关系。”

国际大型金融机构雇用中国高官子女的例子不胜枚举。比较有名的包括2004年,瑞银集团(UBS)出巨资将前中国政协主席李瑞环的儿子李振智从美林证券(Merrill Lynch)挖走,年薪高达1000万美元。而当时作为新手的李振智仅在美林任职一年。

*官二代独钟金融*

与大多数赴海外求学的中国学生不同的是,有背景的中国高官子女一般都选择金融领域。曼达林基金(Mandarin Capital Partners)合伙创始人傅格礼(Alberto Forchielli)说:“金融领域是官二代的最佳选择。他们不学医、不学建筑。他们主要学商科,目标就是进军金融业,要么是去一家投行,要么就选择进入私募股权公司。这非常普遍,因为做金融被认为是非常成功、非常赚钱的行业。” 傅格礼曾毕业于哈佛商学院,他目前还是中欧国际商学院上海企业咨询顾问委员会成员。

西方投行雇用中国精英阶层子女当然也有比较充分的理由。Weiss Berzowski Brady LLP律师事务所的商业律师石明轩(Charles Stone)说:“问题是很多太子党,他们原本非常优秀,他们受到了非常好的教育,他们上哈佛大学商学院等等。我们(美国)的公司认为,如果哈佛要,我们当然也要。” 石明轩还兼任北京大学民营经济研究院教授。

*华尔街看重官二代人脉关系*

但显然,西方大型金融机构更为看重的是富二代、官二代在中国强大的人脉关系。这些公司希望借此敲开中国金融市场的大门,因为聘请高官的子女或亲属作顾问或雇员可以帮助它们突破中国金融市场的层层阻力和限制。“关键在于,中国国家指导的资本主义使得关系资本主义成为美国要打通这些由国家垄断和国家控制的行业的一个敲门砖。”纽约城市大学的夏明说。

不过,这些高官的后代往往不会在某一家国际投资银行做太久。“他们往往是拿到一个比较低的职位,做几年后就离开。他们不会一直干下去。” 傅格礼说。

*官二代把华尔街当跳板*

随着中国经济地位的提高,精英子弟先在国际投行镀金然后回国创立自己的风险投资公司或私募股权公司已经成为他们成功发迹的模式。前面提到的李瑞环长子李振智在麻省理工学院斯隆管理学院获得MBA学位后,曾先后就职于美林和瑞银,后自立门户。李瑞环的次子李振福在辞去诺华制药(Novartis)中国区总裁后于2011年初创立私募基金“德福资本”。

前全国人大常委会委员长吴邦国的女婿冯绍东2008年离开美林后成立了中广核产业基金。冯绍东在2006年帮助美林获得中国工商银行在香港上市承销权的运作中发挥了关键作用。工行上市在当时是有史以来最大的首次公开发行(IPO)。

温家宝的前任朱镕基的长子朱云来曾就读于芝加哥德保罗大学(DePaul University),获得会计硕士学位。他先后在安达信和瑞士信贷第一波士顿(Credit Suisse First Boston)工作,90年代末回国进入中国国际金融有限公司(中金公司)。

高官子女不在国际投行做久有诸多原因,但最重要的是捞不到太多油水。 “中国领导人的子女,如果他们在美国留下来,一方面美国是一个成熟的市场,没有爆发的机会,”夏明说,“另一方面,如果他们在美国长期任职下去的话,基本上最后也就是一个中高层的职务,那么也不会带来暴利。”

华盛顿 — 美国证券交易委员会(SEC)调查摩根大通(JP Morgan Chase)是否通过雇用中国高官子女以获得在中国丰厚业务的时机令人颇感费解。华尔街投行的此类做法已经有至少二十年的历史。

但《中国行将崩溃》一书作者章家敦却认为,美国政府早该出手了。他说:“我认为我们不应该对这个调查感到吃惊。实际上,唯一让人惊讶的是联邦政府怎么会拖这么久才开始真正着手去审视这个问题。”

有分析指出,美国监管机构对华尔街的这一行为早有察觉,只是一直苦于找不到确凿证据。美国证交会此次出手或许是已经找到了突破口。

但Weiss Berzowski Brady LLP律师事务所的商业律师石明轩(Charles Stone)认为,媒体对SEC调查摩根大通做出了过度解读。他说:“我们5月份已经知道,美国的官员已经说过,他们可能要把摩根大通拿来作个例子。(他们)现在在中国雇用太子党的问题很可能是跟以前的问题有关系。”

摩根大通的确最近一直麻烦不断,特别是该公司去年在“伦敦鲸”(London Whale)交易爆仓事件中对金融衍生品押注失败,造成60亿美元的交易损失。这一事件引发了美国国会和行政监管机构对摩根大通的一系列调查。

但无论如何,调查把中国的腐败问题再次展现在世人眼前。章家敦认为,华尔街投行为获得生意而雇用高官后代的做法折射出中国政治经济的结构性问题。

“当然,世界各地的银行都会雇用有关系的人,但这在中国更为普遍,”章家敦说,“这是中国经济中一个结构性问题。中国拥有一个自上而下的政治体制。只要共产党仍然维持一党专制的话,这个体制就不会转变成一个开放、透明和以市场为主导的体制。”

长期以来,中国作为一个巨大的市场一直让西方企业爱恨交加。西方企业为打入中国市场而不得不入乡随俗地遵循中国商界和政界的各项潜规则。中国推行的以国家主导的权贵资本主义使得裙带之风盛行。在中国做生意,往往不是拼实力,而是拼关系“硬不硬”。

美国对摩根大通雇用中国高官子女的调查从某种意义上反应出美国对中国关系资本主义模式的担忧。纽约城市大学的政治学教授夏明说:“美国从某种程度上意识到,尤其是战略层次上意识到,中国的资本主义模式会对全球的投资环境,对全球的商业和资本运行的环境都会带来巨大的威胁。对美国和整个西方的生活方式都会进行某种腐蚀。所以我觉得,现在西方的政界和商界,甚至在普通老百姓的层面上形成越来越强烈的对中国资本抱有怀疑、抵触和仇视的情绪。”

曼达林基金(Mandarin Capital Partners)合伙创始人傅格礼(Alberto Forchielli)也认为,美国证交会对摩根大通的调查突显美国上下弥漫的一股对中国的不利氛围。他说:“我认为美国现在整体上对中国的氛围都不好。这是肯定的。”傅格礼1981年毕业于哈佛商学院,他目前还担任中欧国际商学院上海企业咨询顾问委员会成员。

与此同时,华尔街同中国的联系正在减少。纽约城市大学的夏明说:“我认为,西方的投资银行,尤其是以华尔街为首基本上是在非常谨慎的把它们在中国的投资紧缩。所以我们看到,包括高盛、摩根士丹利在内的投行都把它们在中国的一些标志性建筑和房产脱手。在最近一两年,外资、尤其是美元逃离中国市场是在加剧。”

夏明表示,华尔街的银行家们非常精明,当他们意识到他们无法再从中国市场捞取好处的时候,就会转战其它新兴市场。“应该说,华尔街和中南海的蜜月已经破裂。我觉得这种破裂会带来巨大的政治后果。这种政治后果不仅牵扯到腐败问题,而且会牵扯到最根本的中国奇迹还能不能维护下去,中国的模式会不会最终破产的问题。”

由于中国新一代领导人上台以来一直迟迟未能推出关键的改革措施,再加上以朱云来、温云松为代表的“红色贵族”对中国金融市场的垄断让华尔街对中国越来越失望。这似乎也为美国监管部门过问有关的腐败问题提供了契机,因为在夏明看来,美国证交会选择在此时调查摩根大通涉嫌腐败将不至影响到华尔街在中国的根本利益。

华盛顿 — 美国政府根据联邦法律《反海外腐败法》(Foreign Corrupt Practices Act) 对摩根大通雇佣中国高官子女展开调查。但是观察人士指出,这一行动其实已经是马后炮,因为最近几年,中共太子党对于华尔街投资银行来说,价值已经大大缩水。在失去了华尔街的青睐之后,中共高官的一些子女开始独辟蹊径,回中国,尤其是香港,打造自己的金融帝国。

和张曦曦和唐晓宁一样,很多“太子党”都已经离开了华尔街银行,转而涉足私募基金。例如,前国家总理温家宝的儿子温云松在2005年创立了新天域资本公司 (New Horizon Capital)。根据英国《金融时报》报道,这家公司管理着数十亿美元的资金,投资方包括了德意志银行 (Deutsche Bank)、摩根大通 (JPMorgan Chase & Co.)、以及瑞银 (UBS) 等。而前政治局常委李瑞环的儿子李振福也创立了德福资本 (GL Capital Group) 并担任首席执行官。

预期最早今年上市的阿里巴巴是中国最大的电子商务公司,去年包括博裕资本 (Boyu Capital)、中国投资有限责任公司 (China Investment Corp.)、 中信资本 (CITIC Capital)、国家开发银行 (China Development Bank) 在内的投资者收购了阿里巴巴集团5.6%的股份。前国家主席江泽民的孙子江志成正是博裕资本的合伙人之一,1986年出生的江志成毕业于哈佛大学经济系。博裕资本在2010年注册,预计将在2013年晚些时候推出第二期基金,筹资目标是15亿美元。

包括江志成在内,很多“太子党”都毕业于美国或欧洲名校,例如,温云松是美国西北大学凯洛管理学院 (Kellogg School of Management) 的工商管理硕士、李振福曾在美国芝加哥大学读工商管理,但是章家敦 (Gordon Chang) 认为他们也从家庭关系中受惠。他说:“这些‘太子党’开始成立自己的公司,并利用他们的关系,包括他们的父母以及父母的朋友等关系,在体制中获益。中国政治体制的本质就是要靠关系,你认识什么人,而不是主要靠你的能力。”

除了自创私募基金外,很多“太子党”也任职于国企参与的金融机构。纽约城市大学 (The City University of New York) 政治学 (Political Science and Global Affairs) 教授夏明 (Ming Xia) 说:“中国管理资本的体系是一个高度中央集权化的体系。高干的子女抓紧了非常好的一个机会,他们被西方国家雇用后,积累了在投行的经验后,正好中国出现了大量的过剩资本。这表现在中国的外汇储备达到三万亿,中国的外汇储备以及中国在美国买的国债等都需要大量的人来管理,所以成立了中金公司等来管理这些资产。”

中国国际金融有限公司 (China International Capital Corporation Limited.) ,简称中金公司 (CICC),成立于1995年7月,是中国第一家合资投行,注册资本是2.25亿美元。中金公司的首个大型项目是中国电信(香港)(现中国移动)42亿美元的海外首次公开发行。2004年,前总理朱鎔基的长子朱云来出任中金公司的首席执行官。

此外,前人大委员长吴邦国的女婿冯绍东以及现任政治局常委刘云山的儿子刘乐飞也分别担任中广核产业投资基金总裁和中信产业基金的董事长兼首席执行官。

对于如何管理中国的外汇储备等资产,夏明教授认为:“显然他们也只能相信自己的子女,所以这样的话大量高干子女就利用这个机会在推动和利用中国经济的金融化和货币化,一方面来维持政权的运作,另一方面也在捞取自己的私利。”

中国有越来越多的国企投行和基金,这对华尔街投行在中国的盈利有一定影响。据《华尔街日报》报道,中国公司支付给华尔街的首次公开募股 (Initial Public Offering) 费用已经从2012年的6.52亿美金降低到2013年同期的7, 700万美金。波士顿咨询公司(Boston Consulting Group) 的资深合伙人兼董事总经理邓俊豪 (Tjun Tang) 也认为中国“太子党”对于华尔街已经没有那么大的价值了。

另一方面,中国政治的变动也会对股市价格产生影响。据《华尔街日报》报道,在薄熙来事件发生后,中国光大集团股票的成交量下跌了10%,薄熙来的哥哥薄熙永曾任该集团的副主席。这次美国证券交易委员会 (The Securities and Exchange Commission) 对摩根大通雇用两名中国政界高层子女的调查也令摩根大通的股价下跌。

在美国政府对摩根大通进行贪腐调查的同时,中国近期也对一些外资企业是否违反《反垄断法》加强调查。章家敦说:“我认为这主要是为了帮助国企。因为外企已经在中国的市场有很大的竞争力,北京不希望看到国企的市场份额减少。北京要把机会留给国企,因为国企为政府带来收入,并且也是中共的支柱。”

夏明教授也认同,这从某种程度上是中国为保护国企的行为,因为经济改革到了一定程度,有可能危及中国政治体制。中国很多行业都还是被国企垄断,诸如石油、电信、银行等。

据悉,摩根大通也已聘请纽约宝维斯律师事务所(Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP)对其香港分行的招聘情况进行内部调查。

https://www.letscorp.net/archives/54344

其他资料来源:https://www.voachinese.com/a/wallstreet-princelings-20130823/1735753.html

https://www.voachinese.com/a/china-princelings-wall-streets-2/1737535.html

https://www.voacantonese.com/a/wall-street-chinese-pricelings/1739482.html

One has to go back to the Gilded Age to find business in such a dominant political position in American politics. While it is true that even in the more pluralist 1950s and 1960s, political representation tilted towards the well-off, lobbying was almost balanced by today’s standards. Labor unions were much more important, and the public-interest groups of the 1960s were much more significant actors. And very few companies had their own Washington lobbyists prior to the 1970s. To the extent that businesses did lobby in the 1950s and 1960s (typically through associations), they were clumsy and ineffective. “When we look at the typical lobby,” concluded three leading political scientists in their 1963 study, American Business and Public Policy, “we find its opportunities to maneuver are sharply limited, its staff mediocre, and its typical problem not the influencing of Congressional votes but finding the clients and contributors to enable it to survive at all.”

3,财团们的游说质量不断自我强化,相对于其他反对力量,已经成为了压倒性的力量。一个人只有回到镀金时代才能再次看到商业公司绝对主导美国政治的情形。的确即使是在更多数决定的1950s和1960s,政治代表也向富人倾斜,但按照今天的标准来看游说是几乎平衡的。独立工会更为重要,1960s公共利益组织是更为明显的表演者。1970s时只有很少的公司在华盛顿有他们自己的游说者。在1950s和1960s商业公司的确进行了游说(典型的是通过协会),这些游说是愚蠢的和无效的。“当我们查看典型的游说时,”三位领导地位的政治科学家们在1963年的研究《美国的商业和公共政策》中总结道,“我们发现谨慎行动者们被严格限制,它的雇员很平庸,而典型问题不是影响国会投票者,而是找到能够维持其存活的客户和捐献者。”

Things are quite different today. The evolution of business lobbying from a sparse reactive force into a ubiquitous and increasingly proactive one is among the most important transformations in American politics over the last 40 years. Probing the history of this transformation reveals that there is no “normal” level of business lobbying in American democracy. Rather, business lobbying has built itself up over time, and the self-reinforcing quality of corporate lobbying has increasingly come to overwhelm every other potentially countervailing force. It has also fundamentally changed how corporations interact with government—rather than trying to keep government out of its business (as they did for a long time), companies are now increasingly bringing government in as a partner, looking to see what the country can do for them.

一到这个季节,空气里就充满了焦虑的气味。

去往楼顶中考辅导班的学生,使得电梯突然紧张起来。挤在稚嫩面孔里的老住户,只好小心收紧身体,屏息与之共上下。这些准备考初中的孩子,寄身塔楼楼顶那幢复式结构房子,每日成群结队活动。

他们一律戴近视眼镜,身形歪斜,脸上很少映现少年的光泽,看人的眼神多是飘忽不定。他们吃住在辅导速成班里,接受强化训练,大人为他们交了数千元学费。住户们一眼即可辨别出那些家长,因为他们眼里写满了期待与惶惑。

去小区鞋屋擦皮鞋,四十来岁的老板娘正在训斥儿子:

“为你花这么多钱,你还偷偷玩游戏!你对得起谁?我擦一双鞋才挣七块五,你一小时就要三百。你算过没有,我这双手得擦够五十双臭鞋,才能给你请一对一老师。”

呆头呆脑的五年级学生低头不语。

这对来自保定的夫妻,租用一间二十平米的屋子,以擦鞋擦沙发谋生,他们已经扎根小区十馀年。原本是三人经营,丈夫上门擦洗皮沙发,妻子管店,妻子一个阴郁而枯瘦的弟弟负责擦鞋。租金从九百元涨到三千元,养不起人,老板娘只好让弟弟出外打工。

我是看着他们的后代从一个虎头虎脑的小孩,一步步长成胖乎乎的眼镜男,清澈的眸子一变而为游弋、空洞的眼神。

“考不上好初中,就输了。我们输不起啊。”

她眼里浮起南中国海般浩荡的焦虑。

千里外的老家,大弟为儿子学好奥数,高价请了研究生一对一辅导。幺弟春节就托人为女儿补课,想让女儿考上大学。或许是压力过大,小时候活泼的侄女,一脸疙瘩,身子几乎缩成熊猫状。

一个在西部四线城市工作的朋友,女儿一个月后也将步入高考战场。原本不用功的孩子,突然意识到机会的宝贵,逼迫母亲为自己报贵族辅导班,每天三小时课程,收费六百元,一个十天短期班竟需六千元。夫妻俩一月的收入也就这么多。女儿平日上各种补习班,每年要花费一万多元。值不值得花这么多钱,一家人为此大吵一架,父女俩结成花钱同盟,掌管家庭财权的妻子只好认输,她明白又要过一段苦日子了。

攥紧命运之手!决战高考!

这是涂抹在无数高考工厂墙壁上的动员令。

许多家长明知道大学毕业也没多大用,还得托关系找工作,但还是决意拼死一搏,将孩子和钱财送入产业化怪兽张开的饕餮大嘴里。省吃俭用的血汗钱,就这样被专横的教育悉数吞噬。孩子毁了,父母累了穷了,这就是现实。

在中国,自一个生命呱呱坠地起,父母就开始了不见尽头的马拉松比赛,直到身心俱衰,才有可能卸下这泰山般的重负。在现有教育制度面前,家长们如同一头头被点着屁股的斗牛,日复一日进行痛苦的狂奔——浇在尾巴上的汽油,足够烧十几年而不竭。

漫山遍野的孩奴,遮蔽了太阳的光辉。

这是一场人为设定的乱局。

就业、任用对文凭的要求,规定了教育的根本属性——提供缴费者所需要的标准证书。一个显见的事实是,中国式的教育,只是为了庞大的证书需求而存在。

畸形发展的产业化教育制造了天量证书,文凭的贬值自然不可避免。本来各有所用的文凭,依次轮番贬值,专科,本科,研究生,博士生,博士后。每一个为了谋取较好收益的个体,不得不倾力参与瘟疫式的文凭升级拼搏,专升本,本升研,研升博……专科贱,本科不值钱,研究生满街走,博士帽随风飘扬。

因为权力和人情的腐蚀作用,用人单位最后大都采用惟文凭是举的录取原则。在外人看来,这恰恰是其唯一公平的地方,因而更加热衷于参与文凭竞争。

在洞悉此国秘密的人眼里,文凭只是个道具,它仅仅抬高了准入门槛。因为同级别文凭竞争背后,就是赤裸裸的关系博弈:谁拥有或能撬动权力关系,以及谁支付的贿赂价码(含最管用的性贿赂)更具有竞争力。官后代富后代貌似也参与文凭大战,其实只是走个过场,运用权力或金钱获取所需要的证书,然后一路畅通进入上升快车道,最后高调标榜“能力之外的资本为零”,以此摧毁无权无势者的自信心。老子英雄儿好汉,老子混蛋儿滚蛋。他们要告诉社会的就是这个颠扑不破的血统定律。半个世纪前,热血青年遇罗克就是为了挑战这个新中国的主体真理而付出了生命的代价。

当权贵拿走盘子里的蛋糕之后,剩下的碎渣子由乌泱乌泱的百姓争抢。

为了让参与者全情投入,教育食利阶层设计了一款异常刺激的争斗游戏。打个比方吧,本来大学每年招十人,横竖都只有十人成为幸运儿。如果不加码,游戏就有些乏味,也无从攫取超额利益。于是,他们进行了高超的顶层制度设计,通过不断提高考试难度,不断改变录取标准,让每个人都惶惶不安,因为担心自己被剔除,从而永不松懈地参与搏斗。

在课堂教学之外,一整套标榜快速提高成绩的教育培训机构傲然挺立。这些戕害性灵、榨取钱财的吸血工厂,本身即是由权势者开设,或由那些跟权力完成勾兑的人开办。他们和教育当局联手操纵游戏进程,并攫取最大的利益。

在此庞然大物面前,家长和孩子彻底丧失了自尊和自信心。他们沦为可怜的奴隶,就像被毒蛇摄取了灵魂的老鼠,一跳一跳葬身于死亡之口。

教育主管部门每年煞有介事的减负,无不成为培训机构敛财的契机和动力——他们所标榜的减负力度愈大,它们赚取的钱财愈多。猫鼠一家亲,他们活色生香的表演,只是为了蒙蔽旁观者,以此令入局者更加沉浸其中,这是猫鼠游戏的本质。

这是一场政府主导的合法死亡游戏。他们规定了每个家长的生活方式,彻底改变了每个人的命运,还塑造了可怕的国民性格。

“政教合一”制度下的教育垄断,正在无情地窒息中国的生机。

Children’s dining room, Indian Residential School, Edmonton, Alberta. Between 1925-1936. United Church Archives, Toronto, From Mission to Partnership Collection.Prime Minister Stephen Harper, official apology, June 11, 2008

Children’s dining room, Indian Residential School, Edmonton, Alberta. Between 1925-1936. United Church Archives, Toronto, From Mission to Partnership Collection.Prime Minister Stephen Harper, official apology, June 11, 2008

The term residential schools refers to an extensive school system set up by the Canadian government and administered by churches that had the nominal objective of educating Aboriginal children but also the more damaging and equally explicit objectives of indoctrinating them into Euro-Canadian and Christian ways of living and assimilating them into mainstream Canadian society. The residential school system operated from the 1880s into the closing decades of the 20th century. The system forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time and forbade them to acknowledge their Aboriginal heritage and culture or to speak their own languages. Children were severely punished if these, among other, strict rules were broken. Former students of residential schools have spoken of horrendous abuse at the hands of residential school staff: physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological. Residential schools provided Aboriginal students with an inferior education, often only up to grade five, that focused on training students for manual labour in agriculture, light industry such as woodworking, and domestic work such as laundry work and sewing.

Residential schools systematically undermined Aboriginal culture across Canada and disrupted families for generations, severing the ties through which Aboriginal culture is taught and sustained, and contributing to a general loss of language and culture. Because they were removed from their families, many students grew up without experiencing a nurturing family life and without the knowledge and skills to raise their own families. The devastating effects of the residential schools are far-reaching and continue to have significant impact on Aboriginal communities. Because the government’s and the churches’ intent was to eradicate all aspects of Aboriginal culture in these young people and interrupt its transmission from one generation to the next, the residential school system is commonly considered a form of cultural genocide.

From the 1990s onward, the government and the churches involved—Anglican, Presbyterian, United, and Roman Catholic—began to acknowledge their responsibility for an education scheme that was specifically designed to “kill the Indian in the child.” On June 11, 2008, the Canadian government issued a formal apology in Parliament for the damage done by the residential school system. In spite of this and other apologies, however, the effects remain.

European settlers in Canada brought with them the assumption that their own civilization was the pinnacle of human achievement. They interpreted the socio-cultural differences between themselves and the Aboriginal peoples as proof that Canada’s first inhabitants were ignorant, savage, and—like children—in need of guidance. They felt the need to “civilize” the Aboriginal peoples. Education—a federal responsibility—became the primary means to this end.

Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald commissioned journalist and politician Nicholas Flood Davin to study industrial schools for Aboriginal children in the United States. Davin’s recommendation to follow the U.S. example of “aggressive civilization” led to public funding for the residential school system. “If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young. The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions,” Davin wrote in his 1879 Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds (Davin’s report can be read here.)

In the 1880s, in conjunction with other federal assimilation policies, the government began to establish residential schools across Canada. Authorities would frequently take children to schools far from their home communities, part of a strategy to alienate them from their families and familiar surroundings. In 1920, under the Indian Act, it became mandatory for every Indian child to attend a residential school and illegal for them to attend any other educational institution.1

Male students in the assembly hall of the Alberni Indian Residential School, 1960s. United Church Archives, Toronto, from Mission to Partnership Collection.

Female students in the assembly hall of the Alberni Indian Residential School, 1960s. United Church Archives, Toronto, from Mission to Partnership Collection.

The purpose of the residential schools was to eliminate all aspects of Aboriginal culture. Students had their hair cut short, they were dressed in uniforms, and their days were strictly regimented by timetables. Boys and girls were kept separate, and even siblings rarely interacted, further weakening family ties.2 Chief Bobby Joseph of the Indian Residential School Survivors Society recalls that he had no idea how to interact with girls and never even got to know his own sister “beyond a mere wave in the dining room.”3 In addition, students were strictly forbidden to speak their languages—even though many children knew no other—or to practise Aboriginal customs or traditions. Violations of these rules were severely punished.

Residential school students did not receive the same education as the general population in the public school system, and the schools were sorely underfunded. Teachings focused primarily on practical skills. Girls were primed for domestic service and taught to do laundry, sew, cook, and clean. Boys were taught carpentry, tinsmithing, and farming. Many students attended class part-time and worked for the school the rest of the time: girls did the housekeeping; boys, general maintenance and agriculture. This work, which was involuntary and unpaid, was presented as practical training for the students, but many of the residential schools could not run without it. With so little time spent in class, most students had only reached grade five by the time they were 18. At this point, students were sent away. Many were discouraged from pursuing further education.

Abuse at the schools was widespread: emotional and psychological abuse was constant, physical abuse was meted out as punishment, and sexual abuse was also common. Survivors recall being beaten and strapped; some students were shackled to their beds; some had needles shoved in their tongues for speaking their native languages.4 These abuses, along with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and severely inadequate food and health care, resulted in a shockingly high death toll. In 1907, government medical inspector P.H. Bryce reported that 24 percent of previously healthy Aboriginal children across Canada were dying in residential schools.5 This figure does not include children who died at home, where they were frequently sent when critically ill. Bryce reported that anywhere from 47 percent (on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta) to 75 percent (from File Hills Boarding School in Saskatchewan) of students discharged from residential schools died shortly after returning home.6

In addition to unhealthy conditions and corporal punishment, children were frequently assaulted, raped, or threatened by staff or other students. During the 2005 sentencing of Arthur Plint, a dorm supervisor at the Port Alberni Indian Residential School convicted of 16 counts of indecent assault, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called Plint a “sexual terrorist.” Hogarth stated, “As far as the victims were concerned, the Indian residential school system was nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia.”7

The extent to which Department of Indian Affairs and church officials knew of these abuses has been debated. However, the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples and Dr John Milloy, among others, concluded that church and state officials were fully aware of the abuses and tragedies at the schools. Some inspectors and officials at the time expressed alarm at the horrifying death rates, yet those who spoke out and called for reform were generally met with silence and lack of support.8 The Department of Indian Affairs would promise to improve the schools, but the deplorable conditions persisted.9

Some former students have fond memories of their time at residential schools, and certainly some of the priests and nuns who ran the schools treated the students as best they could given the circumstances. But even these “good” experiences occurred within a system aimed at destroying Aboriginal cultures and assimilating Aboriginal students.

“Sister Marie Baptiste had a supply of sticks as long and thick as pool cues. When she heard me speak my language, she’d lift up her hands and bring the stick down on me. I’ve still got bumps and scars on my hands. I have to wear special gloves because the cold weather really hurts my hands. I tried very hard not to cry when I was being beaten and I can still just turn off my feelings…. And I’m lucky. Many of the men my age, they either didn’t make it, committed suicide or died violent deaths, or alcohol got them. And it wasn’t just my generation. My grandmother, who’s in her late nineties, to this day it’s too painful for her to talk about what happened to her at the school.”

– Musqueam Nation former chief George Guerin,

Kuper Island school

Stolen from our Embrace, p 62

European officials of the 19th century believed that Aboriginal societies were dying out and that the only hope for Aboriginal people was to convert them to Christianity, do away with their cultures, and turn them into “civilized” British subjects—in short, assimilate them. By the 1950s, it was clear that assimilation was not working. Aboriginal cultures survived, despite all the efforts to destroy them and despite all the damage done. The devastating effects of the residential schools and the particular needs and life experiences of Aboriginal students were becoming more widely recognized.10 The government also acknowledged that removing children from their families was severely detrimental to the health of the individuals and the communities involved. In 1951, with the amendments to the Indian Act, the half-day work/school system was abandoned.11

The government decided to allow Aboriginal children to live with their families whenever possible, and the schools began hiring more qualified staff.12 In 1969, the Department of Indian Affairs took exclusive control of the system, marking an end to church involvement. Yet the schools remained underfunded and abuse continued.13 Many teachers were still very much unqualified; in fact, some had not graduated high school themselves.14

In the meantime, the government decided to phase out segregation and begin incorporating Aboriginal students into public schools. Although these changes saw students reaching higher levels of education, problems persisted. Many Aboriginal students struggled in their adjustment to public school and to a Eurocentric system in which Aboriginal students faced discrimination by their non-Aboriginal peers. Post-secondary education was still considered out of reach for Aboriginal students, and those students who wanted to attend university were frequently discouraged from doing so.15

The process to phase out the residential school system and other assimilation tactics was slow and not without reversals. In the 1960s, the system’s closure gave way to the “Sixties Scoop,” during which thousands of Aboriginal children were “apprehended” by social services and removed from their families. The “Scoop” spanned roughly the two decades it took to phase out the residential schools, but child apprehensions from Aboriginal families continue to occur in disproportionate numbers. In part, this is the legacy of compromised families and communities left by the residential schools.

The last residential school did not close its doors until 1986.16

It is clear that the schools have been, arguably, the most damaging of the many elements of Canada’s colonization of this land’s original peoples and, as their consequences still affect the lives of Aboriginal people today, they remain so.

—John S. Milloy, A National Crime

The residential school system is viewed by much of the Canadian public as part of a distant past, disassociated from today’s events. In many ways, this is a misconception. The last residential school did not close its doors until 1986. Many of the leaders, teachers, parents, and grandparents of today’s Aboriginal communities are residential school survivors. There is, in addition, an intergenerational effect: many descendents of residential school survivors share the same burdens as their ancestors even if they did not attend the schools themselves. These include transmitted personal trauma and compromised family systems, as well as the loss in Aboriginal communities of language, culture, and the teaching of tradition from one generation to another.

According to the Manitoba Justice Institute, residential schools laid the foundation for the epidemic we see today of domestic abuse and violence against Aboriginal women and children.17 Generations of children have grown up without a nurturing family life. As adults, many of them lack adequate parenting skills and, having only experienced abuse, in turn abuse their children and family members. The high incidence of domestic violence among Aboriginal families results in many broken homes, perpetuating the cycle of abuse and dysfunction over generations.

Many observers have argued that the sense of worthlessness that was instilled in students by the residential school system contributed to extremely low self-esteem. This has manifested itself in self-abuse, resulting in high rates of alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide. Among First Nations people aged 10 to 44, suicide and self-inflicted injury is the number one cause of death, responsible for almost 40 percent of mortalities.18 First Nations women attempt suicide eight times more often than other Canadian women, and First Nations men attempt suicide five times more often than other Canadian men.19 Some communities experience what have been called suicide epidemics.

Many Aboriginal children have grown up feeling that they do not belong in “either world”: they are neither truly Aboriginal nor part of the dominant society. They struggle to fit in but face discrimination from both societies, which makes it difficult to obtain education and skills. The result is poverty for many Aboriginal people. In addition, the residential schools and other negative experiences with state-sponsored education have fostered mistrust of education in general, making it difficult for Aboriginal communities and individuals to break the cycle of poverty.

In the 1980s, residential school survivors began to take the government and churches to court, suing them for damages resulting from the residential school experience. In 1988, eight former students of St. George’s Indian Residential School in Lytton, B.C., sued a priest, the government, and the Anglican Church of Canada in Mowatt v. Clarke. Both the Anglican Church and the government admitted fault and agreed to a settlement. Another successful case followed in 1990, made by eight survivors from St. Joseph’s school, in Williams Lake, against the Catholic Church and the federal government.20

The court cases continued, and in 1995, thirty survivors from the Alberni Indian Residential School filed charges against Arthur Plint, a dorm supervisor who had sexually abused children under his care. In addition to convicting Plint, the court held the federal government and the United Church responsible for the wrongs committed.

The Anglican Church publicly apologized for its role in the residential school system in 1993, the Presbyterian Church in 1994, and the United Church in 1998. Most recently, in April 2009, Assembly of First Nations leader Phil Fontaine accepted an invitation from Pope Benedict XVI and travelled to Vatican City with the goal of obtaining an apology from the Catholic Church for its role in the residential school system. After the meeting, the Vatican issued a press release stating that “the Holy Father expressed his sorrow at the anguish caused by the deplorable conduct of some members of the Church and he offered his sympathy and prayerful solidarity.”21

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions are used around the world in situations where countries want to reconcile and resolve policies or practices, typically of the state, that have left legacies of harm. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a non-adversarial way to allow residential school survivors to share their stories and experiences and, according to the Department of Indian Affairs, will “facilitate reconciliation among former students, their families, their communities and all Canadians” for “a collective journey toward a more unified Canada.

Meanwhile, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples had been interviewing Indigenous people across Canada about their experiences. The commission’s report, published in 1996, brought unprecedented attention to the residential school system—many non-Aboriginal Canadians did not know about this chapter in Canadian history. In 1998, based on the commission’s recommendations and in light of the court cases, the Canadian government publicly apologized to former students for the physical and sexual abuse they suffered in the residential schools. The Aboriginal Healing Fund was established as a $350 million government plan to aid communities affected by the residential schools. However, some Aboriginal people felt the government apology did not go far enough, since it addressed only the effects of physical and sexual abuse and not other damages caused by the residential school system.

In 2005, the Assembly of First Nations launched a class action lawsuit against the Canadian government for the long-lasting harm inflicted by the residential school system. In 2006, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was reached by the parties in conflict and became the largest class action settlement in Canadian history.22 In September 2007, the federal government and the churches involved agreed to pay individual and collective compensation to residential school survivors. The government also pledged to create measures and support for healing and to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Indian Residential School Survivors Society was formed in 1994 by the First Nations Summit in British Columbia and was officially incorporated in 2002 to provide support for survivors and communities in the province throughout the healing process and to educate the broader public. The Survivors Society provides crisis counselling, referrals, and healing initiatives, as well as acting as a resource for information, research, training, and workshops.23 It was clear that a similar organization was needed at the national level, and in 2005, the National Residential School Survivors Society was incorporated.24

I have just one last thing to say. To all of the leaders of the Liberals, the Bloc and NDP, thank you, as well, for your words because now it is about our responsibilities today, the decisions that we make today and how they will affect seven generations from now.

My ancestors did the same seven generations ago and they tried hard to fight against you because they knew what was happening. They knew what was coming, but we have had so much impact from colonization and that is what we are dealing with today.

Women have taken the brunt of it all.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here at this moment in time to talk about those realities that we are dealing with today.

What is it that this government is going to do in the future to help our people? Because we are dealing with major human rights violations that have occurred to many generations: my language, my culture and my spirituality. I know that I want to transfer those to my children and my grandchildren, and their children, and so on.

What is going to be provided? That is my question. I know that is the question from all of us. That is what we would like to continue to work on, in partnership.

Nia:wen. Thank you.

—Beverley Jacobs, President, Native Women’s Association of Canada, June 11, 2008

Read the full transcript and watch the video here.

We feel that the acceptability of the apology is very much a personal decision of residential school survivors. The Nisga’a Nation will consider the sincerity of the Prime Minister’s apology on the basis of the policies and actions of the government in the days and years to come. Only history will determine the degree of its sincerity.

—Kevin McKay, Chair of the Nisga’a Lisims Government, June 12, 2008

In September 2007, while the Settlement Agreement was being put into action, the Liberal government made a motion to issue a formal apology. The motion passed unanimously. On June 11, 2008, the House of Commons gathered in a solemn ceremony to publicly apologize for the government’s involvement in the residential school system and to acknowledge the widespread impact this system has had among Aboriginal peoples. You can read the official statement and responses to it by Aboriginal organizations here. The apology was broadcast live across Canada (watch it here).

The federal government’s apology was met with a range of responses. Some people felt that it marked a new era of positive federal government–Aboriginal relations based on mutual respect, while others felt that the apology was merely symbolic and doubted that it would change the government’s relationship with Aboriginal peoples.

Although the apologies and acknowledgements made by governments and churches are important steps forward in the healing process, Aboriginal leaders have said that such gestures are not enough without supportive action. Communities and residential school survivor societies are undertaking healing initiatives, both traditional and non-traditional, and providing opportunities for survivors to talk about their experiences and move forward to heal and to create a positive future for themselves, their families, and their communities.

We are on the threshold of a new beginning where we are in control of our own destinies. We must be careful and listen to the voices that have been silenced by fear and isolation. We must be careful not to repeat the patterns or create the oppressive system of the residential schools. We must build an understanding of what happened to those generations that came before us.

— Wayne Christian, Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School, 2000