Residential Schools

Children’s dining room, Indian Residential School, Edmonton, Alberta. Between 1925-1936. United Church Archives, Toronto, From Mission to Partnership Collection.Prime Minister Stephen Harper, official apology, June 11, 2008

Children’s dining room, Indian Residential School, Edmonton, Alberta. Between 1925-1936. United Church Archives, Toronto, From Mission to Partnership Collection.Prime Minister Stephen Harper, official apology, June 11, 2008

What was the Indian residential school system?

The term residential schools refers to an extensive school system set up by the Canadian government and administered by churches that had the nominal objective of educating Aboriginal children but also the more damaging and equally explicit objectives of indoctrinating them into Euro-Canadian and Christian ways of living and assimilating them into mainstream Canadian society. The residential school system operated from the 1880s into the closing decades of the 20th century. The system forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time and forbade them to acknowledge their Aboriginal heritage and culture or to speak their own languages. Children were severely punished if these, among other, strict rules were broken. Former students of residential schools have spoken of horrendous abuse at the hands of residential school staff: physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological. Residential schools provided Aboriginal students with an inferior education, often only up to grade five, that focused on training students for manual labour in agriculture, light industry such as woodworking, and domestic work such as laundry work and sewing.

Residential schools systematically undermined Aboriginal culture across Canada and disrupted families for generations, severing the ties through which Aboriginal culture is taught and sustained, and contributing to a general loss of language and culture. Because they were removed from their families, many students grew up without experiencing a nurturing family life and without the knowledge and skills to raise their own families. The devastating effects of the residential schools are far-reaching and continue to have significant impact on Aboriginal communities. Because the government’s and the churches’ intent was to eradicate all aspects of Aboriginal culture in these young people and interrupt its transmission from one generation to the next, the residential school system is commonly considered a form of cultural genocide.

From the 1990s onward, the government and the churches involved—Anglican, Presbyterian, United, and Roman Catholic—began to acknowledge their responsibility for an education scheme that was specifically designed to “kill the Indian in the child.” On June 11, 2008, the Canadian government issued a formal apology in Parliament for the damage done by the residential school system. In spite of this and other apologies, however, the effects remain.

What led to the residential schools?

European settlers in Canada brought with them the assumption that their own civilization was the pinnacle of human achievement. They interpreted the socio-cultural differences between themselves and the Aboriginal peoples as proof that Canada’s first inhabitants were ignorant, savage, and—like children—in need of guidance. They felt the need to “civilize” the Aboriginal peoples. Education—a federal responsibility—became the primary means to this end.

Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald commissioned journalist and politician Nicholas Flood Davin to study industrial schools for Aboriginal children in the United States. Davin’s recommendation to follow the U.S. example of “aggressive civilization” led to public funding for the residential school system. “If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young. The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions,” Davin wrote in his 1879 Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds (Davin’s report can be read here.)

In the 1880s, in conjunction with other federal assimilation policies, the government began to establish residential schools across Canada. Authorities would frequently take children to schools far from their home communities, part of a strategy to alienate them from their families and familiar surroundings. In 1920, under the Indian Act, it became mandatory for every Indian child to attend a residential school and illegal for them to attend any other educational institution.1

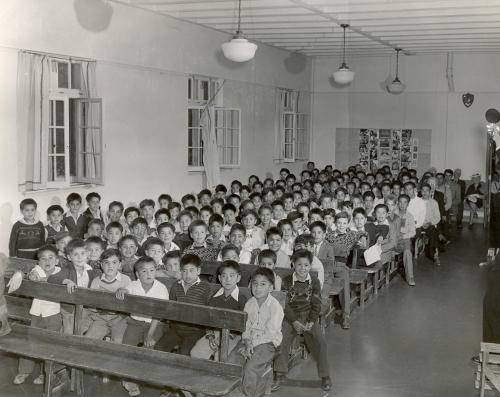

Male students in the assembly hall of the Alberni Indian Residential School, 1960s. United Church Archives, Toronto, from Mission to Partnership Collection.

Female students in the assembly hall of the Alberni Indian Residential School, 1960s. United Church Archives, Toronto, from Mission to Partnership Collection.

Living conditions at the residential schools

The purpose of the residential schools was to eliminate all aspects of Aboriginal culture. Students had their hair cut short, they were dressed in uniforms, and their days were strictly regimented by timetables. Boys and girls were kept separate, and even siblings rarely interacted, further weakening family ties.2 Chief Bobby Joseph of the Indian Residential School Survivors Society recalls that he had no idea how to interact with girls and never even got to know his own sister “beyond a mere wave in the dining room.”3 In addition, students were strictly forbidden to speak their languages—even though many children knew no other—or to practise Aboriginal customs or traditions. Violations of these rules were severely punished.

Residential school students did not receive the same education as the general population in the public school system, and the schools were sorely underfunded. Teachings focused primarily on practical skills. Girls were primed for domestic service and taught to do laundry, sew, cook, and clean. Boys were taught carpentry, tinsmithing, and farming. Many students attended class part-time and worked for the school the rest of the time: girls did the housekeeping; boys, general maintenance and agriculture. This work, which was involuntary and unpaid, was presented as practical training for the students, but many of the residential schools could not run without it. With so little time spent in class, most students had only reached grade five by the time they were 18. At this point, students were sent away. Many were discouraged from pursuing further education.

Abuse at the schools was widespread: emotional and psychological abuse was constant, physical abuse was meted out as punishment, and sexual abuse was also common. Survivors recall being beaten and strapped; some students were shackled to their beds; some had needles shoved in their tongues for speaking their native languages.4 These abuses, along with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and severely inadequate food and health care, resulted in a shockingly high death toll. In 1907, government medical inspector P.H. Bryce reported that 24 percent of previously healthy Aboriginal children across Canada were dying in residential schools.5 This figure does not include children who died at home, where they were frequently sent when critically ill. Bryce reported that anywhere from 47 percent (on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta) to 75 percent (from File Hills Boarding School in Saskatchewan) of students discharged from residential schools died shortly after returning home.6

In addition to unhealthy conditions and corporal punishment, children were frequently assaulted, raped, or threatened by staff or other students. During the 2005 sentencing of Arthur Plint, a dorm supervisor at the Port Alberni Indian Residential School convicted of 16 counts of indecent assault, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called Plint a “sexual terrorist.” Hogarth stated, “As far as the victims were concerned, the Indian residential school system was nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia.”7

The extent to which Department of Indian Affairs and church officials knew of these abuses has been debated. However, the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples and Dr John Milloy, among others, concluded that church and state officials were fully aware of the abuses and tragedies at the schools. Some inspectors and officials at the time expressed alarm at the horrifying death rates, yet those who spoke out and called for reform were generally met with silence and lack of support.8 The Department of Indian Affairs would promise to improve the schools, but the deplorable conditions persisted.9

Some former students have fond memories of their time at residential schools, and certainly some of the priests and nuns who ran the schools treated the students as best they could given the circumstances. But even these “good” experiences occurred within a system aimed at destroying Aboriginal cultures and assimilating Aboriginal students.

The shift away from the residential school system

“Sister Marie Baptiste had a supply of sticks as long and thick as pool cues. When she heard me speak my language, she’d lift up her hands and bring the stick down on me. I’ve still got bumps and scars on my hands. I have to wear special gloves because the cold weather really hurts my hands. I tried very hard not to cry when I was being beaten and I can still just turn off my feelings…. And I’m lucky. Many of the men my age, they either didn’t make it, committed suicide or died violent deaths, or alcohol got them. And it wasn’t just my generation. My grandmother, who’s in her late nineties, to this day it’s too painful for her to talk about what happened to her at the school.”

– Musqueam Nation former chief George Guerin,

Kuper Island school

Stolen from our Embrace, p 62

European officials of the 19th century believed that Aboriginal societies were dying out and that the only hope for Aboriginal people was to convert them to Christianity, do away with their cultures, and turn them into “civilized” British subjects—in short, assimilate them. By the 1950s, it was clear that assimilation was not working. Aboriginal cultures survived, despite all the efforts to destroy them and despite all the damage done. The devastating effects of the residential schools and the particular needs and life experiences of Aboriginal students were becoming more widely recognized.10 The government also acknowledged that removing children from their families was severely detrimental to the health of the individuals and the communities involved. In 1951, with the amendments to the Indian Act, the half-day work/school system was abandoned.11

The government decided to allow Aboriginal children to live with their families whenever possible, and the schools began hiring more qualified staff.12 In 1969, the Department of Indian Affairs took exclusive control of the system, marking an end to church involvement. Yet the schools remained underfunded and abuse continued.13 Many teachers were still very much unqualified; in fact, some had not graduated high school themselves.14

In the meantime, the government decided to phase out segregation and begin incorporating Aboriginal students into public schools. Although these changes saw students reaching higher levels of education, problems persisted. Many Aboriginal students struggled in their adjustment to public school and to a Eurocentric system in which Aboriginal students faced discrimination by their non-Aboriginal peers. Post-secondary education was still considered out of reach for Aboriginal students, and those students who wanted to attend university were frequently discouraged from doing so.15

The process to phase out the residential school system and other assimilation tactics was slow and not without reversals. In the 1960s, the system’s closure gave way to the “Sixties Scoop,” during which thousands of Aboriginal children were “apprehended” by social services and removed from their families. The “Scoop” spanned roughly the two decades it took to phase out the residential schools, but child apprehensions from Aboriginal families continue to occur in disproportionate numbers. In part, this is the legacy of compromised families and communities left by the residential schools.

The last residential school did not close its doors until 1986.16

Long-term impacts

It is clear that the schools have been, arguably, the most damaging of the many elements of Canada’s colonization of this land’s original peoples and, as their consequences still affect the lives of Aboriginal people today, they remain so.

—John S. Milloy, A National Crime

The residential school system is viewed by much of the Canadian public as part of a distant past, disassociated from today’s events. In many ways, this is a misconception. The last residential school did not close its doors until 1986. Many of the leaders, teachers, parents, and grandparents of today’s Aboriginal communities are residential school survivors. There is, in addition, an intergenerational effect: many descendents of residential school survivors share the same burdens as their ancestors even if they did not attend the schools themselves. These include transmitted personal trauma and compromised family systems, as well as the loss in Aboriginal communities of language, culture, and the teaching of tradition from one generation to another.

According to the Manitoba Justice Institute, residential schools laid the foundation for the epidemic we see today of domestic abuse and violence against Aboriginal women and children.17 Generations of children have grown up without a nurturing family life. As adults, many of them lack adequate parenting skills and, having only experienced abuse, in turn abuse their children and family members. The high incidence of domestic violence among Aboriginal families results in many broken homes, perpetuating the cycle of abuse and dysfunction over generations.

Many observers have argued that the sense of worthlessness that was instilled in students by the residential school system contributed to extremely low self-esteem. This has manifested itself in self-abuse, resulting in high rates of alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide. Among First Nations people aged 10 to 44, suicide and self-inflicted injury is the number one cause of death, responsible for almost 40 percent of mortalities.18 First Nations women attempt suicide eight times more often than other Canadian women, and First Nations men attempt suicide five times more often than other Canadian men.19 Some communities experience what have been called suicide epidemics.

Many Aboriginal children have grown up feeling that they do not belong in “either world”: they are neither truly Aboriginal nor part of the dominant society. They struggle to fit in but face discrimination from both societies, which makes it difficult to obtain education and skills. The result is poverty for many Aboriginal people. In addition, the residential schools and other negative experiences with state-sponsored education have fostered mistrust of education in general, making it difficult for Aboriginal communities and individuals to break the cycle of poverty.

In the 1980s, residential school survivors began to take the government and churches to court, suing them for damages resulting from the residential school experience. In 1988, eight former students of St. George’s Indian Residential School in Lytton, B.C., sued a priest, the government, and the Anglican Church of Canada in Mowatt v. Clarke. Both the Anglican Church and the government admitted fault and agreed to a settlement. Another successful case followed in 1990, made by eight survivors from St. Joseph’s school, in Williams Lake, against the Catholic Church and the federal government.20

The court cases continued, and in 1995, thirty survivors from the Alberni Indian Residential School filed charges against Arthur Plint, a dorm supervisor who had sexually abused children under his care. In addition to convicting Plint, the court held the federal government and the United Church responsible for the wrongs committed.

The Anglican Church publicly apologized for its role in the residential school system in 1993, the Presbyterian Church in 1994, and the United Church in 1998. Most recently, in April 2009, Assembly of First Nations leader Phil Fontaine accepted an invitation from Pope Benedict XVI and travelled to Vatican City with the goal of obtaining an apology from the Catholic Church for its role in the residential school system. After the meeting, the Vatican issued a press release stating that “the Holy Father expressed his sorrow at the anguish caused by the deplorable conduct of some members of the Church and he offered his sympathy and prayerful solidarity.”21

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions are used around the world in situations where countries want to reconcile and resolve policies or practices, typically of the state, that have left legacies of harm. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a non-adversarial way to allow residential school survivors to share their stories and experiences and, according to the Department of Indian Affairs, will “facilitate reconciliation among former students, their families, their communities and all Canadians” for “a collective journey toward a more unified Canada.

Meanwhile, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples had been interviewing Indigenous people across Canada about their experiences. The commission’s report, published in 1996, brought unprecedented attention to the residential school system—many non-Aboriginal Canadians did not know about this chapter in Canadian history. In 1998, based on the commission’s recommendations and in light of the court cases, the Canadian government publicly apologized to former students for the physical and sexual abuse they suffered in the residential schools. The Aboriginal Healing Fund was established as a $350 million government plan to aid communities affected by the residential schools. However, some Aboriginal people felt the government apology did not go far enough, since it addressed only the effects of physical and sexual abuse and not other damages caused by the residential school system.

In 2005, the Assembly of First Nations launched a class action lawsuit against the Canadian government for the long-lasting harm inflicted by the residential school system. In 2006, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was reached by the parties in conflict and became the largest class action settlement in Canadian history.22 In September 2007, the federal government and the churches involved agreed to pay individual and collective compensation to residential school survivors. The government also pledged to create measures and support for healing and to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Indian Residential School Survivors Society was formed in 1994 by the First Nations Summit in British Columbia and was officially incorporated in 2002 to provide support for survivors and communities in the province throughout the healing process and to educate the broader public. The Survivors Society provides crisis counselling, referrals, and healing initiatives, as well as acting as a resource for information, research, training, and workshops.23 It was clear that a similar organization was needed at the national level, and in 2005, the National Residential School Survivors Society was incorporated.24

Official government apology

I have just one last thing to say. To all of the leaders of the Liberals, the Bloc and NDP, thank you, as well, for your words because now it is about our responsibilities today, the decisions that we make today and how they will affect seven generations from now.

My ancestors did the same seven generations ago and they tried hard to fight against you because they knew what was happening. They knew what was coming, but we have had so much impact from colonization and that is what we are dealing with today.

Women have taken the brunt of it all.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here at this moment in time to talk about those realities that we are dealing with today.

What is it that this government is going to do in the future to help our people? Because we are dealing with major human rights violations that have occurred to many generations: my language, my culture and my spirituality. I know that I want to transfer those to my children and my grandchildren, and their children, and so on.

What is going to be provided? That is my question. I know that is the question from all of us. That is what we would like to continue to work on, in partnership.

Nia:wen. Thank you.

—Beverley Jacobs, President, Native Women’s Association of Canada, June 11, 2008

Read the full transcript and watch the video here.

We feel that the acceptability of the apology is very much a personal decision of residential school survivors. The Nisga’a Nation will consider the sincerity of the Prime Minister’s apology on the basis of the policies and actions of the government in the days and years to come. Only history will determine the degree of its sincerity.

—Kevin McKay, Chair of the Nisga’a Lisims Government, June 12, 2008

In September 2007, while the Settlement Agreement was being put into action, the Liberal government made a motion to issue a formal apology. The motion passed unanimously. On June 11, 2008, the House of Commons gathered in a solemn ceremony to publicly apologize for the government’s involvement in the residential school system and to acknowledge the widespread impact this system has had among Aboriginal peoples. You can read the official statement and responses to it by Aboriginal organizations here. The apology was broadcast live across Canada (watch it here).

The federal government’s apology was met with a range of responses. Some people felt that it marked a new era of positive federal government–Aboriginal relations based on mutual respect, while others felt that the apology was merely symbolic and doubted that it would change the government’s relationship with Aboriginal peoples.

Although the apologies and acknowledgements made by governments and churches are important steps forward in the healing process, Aboriginal leaders have said that such gestures are not enough without supportive action. Communities and residential school survivor societies are undertaking healing initiatives, both traditional and non-traditional, and providing opportunities for survivors to talk about their experiences and move forward to heal and to create a positive future for themselves, their families, and their communities.

We are on the threshold of a new beginning where we are in control of our own destinies. We must be careful and listen to the voices that have been silenced by fear and isolation. We must be careful not to repeat the patterns or create the oppressive system of the residential schools. We must build an understanding of what happened to those generations that came before us.

— Wayne Christian, Behind Closed Doors: Stories from the Kamloops Indian Residential School, 2000