Let’s set a scene. You’re with your extended family, and discussion meanders to an observation about you. Someone notes that, “Hey, on Facebook, it looks like you been going to protests — looks like you’ve been casting aspersions on capitalism, American imperialism, Ezra Klein. You’ve been using words like neoliberalism and reading Trotsky. It seems like you’re a socialist — maybe even be a commie?”

让我们设置一个场景。你和你的大家庭在一起,讨论中提到了对你的观察。有人注意到,“嘿,在Facebook上,看起来你一直在抗议—看起来你一直在抨击资本主义,美国帝国主义,Ezra Klein。 你一直在使用新自由主义和正在阅读读托洛茨基这样的词。看起来你是一个社会主义者—甚至可能是一个共产主义者?“

Someone at this gathering immediately responds to this revelation with disdain — maybe a cousin who overdosed on econ classes at college. This cousin turns to address you: “Socialism is all well and good on paper. Caring, sharing, all sounds great. But you’re preaching to the wrong species. Humans aren’t hippies. They’re selfish and care only about themselves — hence war, plunder, exploitation, violence. With the raw materials that are human beings, you’ll never build anything other than what we have today.”

在这次聚会中,有人立即回应这一启示,不屑一顾的—也许是一位在大学里上了过量经济课的堂兄。这位堂兄转过身来对你说:“社会主义在纸面上一切都很好。 关怀,分享,听起来都很棒。 但是你正在向错误的物种布道。人类不是嬉皮士。 他们是自私的,只关心自己—因此有了战争,掠夺,剥削,暴力。拿着组成人类的原材料,除了我们今天所拥有的东西之外,你永远建造不了其他任何东西。“

When confronted with this objection, I’m guessing that most of us respond in roughly the same way — something like, “Look, cuz: the humans you know, they are monsters. Not only because you only hang out with douchebags, but also because you only know ‘capitalist man.’ Capitalist man sucks. But socialist man, on the other hand — he would be caring and compassionate.”

当面对这个反对意见时,我猜我们大多数人都以大致相同的方式回应—比如,“看,因为:你认识的人,他们是怪物。 不仅因为你只和二逼们一起出去玩,还因为你只知道’资本主义者’。资本主义者很糟糕。但另一方面,社会主义者 —他会关心别人和富有同情心。“

Finishing with a flourish, we’d probably say something like, “The bottom line is, there is no such thing as human nature.” Humans are made, they aren’t born.

以一个吸引人的语句作为结尾,我们可能会说,“最重要的是,没有人性这种东西。”人类是被制造的,而不是天生就是如此。

In short, in response to the argument that humans are inherently competitive and selfish, you argued that in fact, there are no attributes or drives that adhere in humans. There is no such thing as a human nature. Let’s call this the “Blank Slate Thesis.”

简而言之,为了回应人类具有内在的竞争性和自私性的论点,你认为事实上,没有任何属性或驱动力可以固定在人类身上。没有人性这东西。 我们称之为“白板理论”。

The Blank Slate Thesis is wrong. It’s the wrong way to confront your cousin’s objection to socialism, and it’s the wrong way to defend the possibly of another type of society.

白板理论是错误的。这是对付堂兄反对社会主义观点的错误方式,而这是捍卫另一种可能的社会的错误方式。

The Moral Problem

道德问题

The Blank Slate Thesis leads socialists into three kinds of insoluble problems; three difficulties that reveal that most of us don’t even believe that there is no such thing as a human nature, even if we’ve made the opposite argument to stubborn cousins. There’s a moral difficulty, there’s an analytical difficulty, and there’s a political difficulty.

白板理论引导社会主义者们陷入三种无法解决的问题; 三个难题表明我们大多数人甚至不相信没有人性这种东西,即使我们对固执的堂兄做出了相反的论证。存在道德上的难题,存在分析上的难题,并且存在政治上的难题。

First, the moral difficulty. The thesis that humans have no inherent human nature makes our moral project incoherent.

一是道德难题。 人类没有固有人性的理论使我们的道德项目模糊不清。

By this, I mean one very simple thing. When you or I look at the world around us and find that something is amiss, that something immoral is afoot, we fixate on certain elemental forms of deprivation.

这么说吧,我的意思是一个非常简单的事情。 当你或我看到周围的世界并发现某些事情不对劲,那些不道德的事情正在发生时,我们会注意某些基本的剥夺形式。

People are deprived of the basic things that they need in order to reproduce themselves comfortably. Many people in this world go to sleep hungry. They’re worried they may not survive their next pregnancy, their next illness, their next marriage. They’re worried that the oceans may rise to flood their home. They work meaningless jobs for petty tyrants. They can’t send their children to decent schools.

人们被剥夺了他们所需要的以便舒适地再生产自己的基本资源。这世界上的很多人都饿着肚子睡觉。他们担心他们可能无法在下次怀孕,下次疾病,下次婚姻中幸存下来。他们担心海洋可能会淹没他们的家园。他们为小暴君们做着毫无意义的工作。他们不能把孩子送到体面的学校。

We agree that these things are terrible, they ought to be eliminated from our world. But you think these things are outrageous because you correctly believe that the people living in these conditions must themselves be outraged.

我们同意这些事情是糟糕的,它们应该从我们的世界中被消除。但是你认为这些事情是令人愤怒的,因为你正确地认为生活在这些环境下的人们他们自己必须被激怒。

You believe that the average human being should not be forced to live impoverished, stunted lives because you impute to the average human being certain unshakeable interests — being fed when hungry, quenched when thirsty, free when dominated.

你相信普通人不应该被迫生活在贫困中,以及发育不良的生活中,因为你把认为人有着均等的不可动摇的利益—饥饿时被喂饱,口渴时能解渴,主导自己时是自由的。

Consider the glorious socialist invocation, “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains.” That’s a universal injunction. And why is that compelling? Because we all know that nobody likes being in chains.

考虑一下这个光荣的社会主义口号,“全世界的工人们团结起来,除了锁链你们没有什么可失去的。”这是一个普遍的命令。为什么这引人注目? 因为我们都知道没有人喜欢被束缚。

The slogan is not, “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains. Unless, in some cultures, people like being in chains, in which case, we demand that those people be allowed to keep their chains.”

口号不是,“全世界的工人们团结起来,你除了锁链没有什么可失去的。 除非在某些文化中,人们喜欢被束缚,在这种情况下,我们要求允许这些人保留他们的锁链。“

This belief that these universal interests exist is rooted in a belief that humans universally are everywhere basically the same. You believe that people are meaningfully animated by their human nature whatever the influence of culture or history on them.

认为这种普遍利益存在的这种信念植根于这样一种信念,即人类普遍在每个地方都是基本相同的。 你相信无论文化或历史对他们的影响如何,他们都有着有意义的本性。

The Analytical Problem

分析问题

So that’s the first point. Our moral projects are normative projects that require a commitment to some model of what human beings demand everywhere by virtue of their very nature.

所以这是第一点。 我们的道德项目是规范性项目,这要求承诺人类因其本性而在所有地方都需要某种模式。

Second, an analytical point. If humans were blank slates, it would be very difficult to make much sense of the laws of motion of human societies. It would lead to an analytical impasse.

第二,一个分析点。 如果人类是白板,那么就很难理解人类社会的运动规律。 这将导致分析陷入僵局。

As Vivek Chibber recently argued, socialists fixate on class because class analysis holds diagnostic and prognostic insight. Both of these claims are versions of a more general claim that socialists make about human history, which is referred to as “historical materialism.”

正如Vivek Chibber最近提出的那样,社会主义者注重阶级,因为阶级分析具有进行诊断和预测的洞察力。 这两种主张都是社会主义者对人类历史的更普遍的主张的版本,这被称为“历史唯物主义”。

The claim is that given certain information about how the total pie in any given society is produced — about who does the producing, who does the appropriating, who owns, who rents, who works — we can make certain inferences about who has power and who is powerless, about who will do well for themselves and who will do poorly.

这一声称是关于任何一个特定社会中的总馅饼是如何产生的—关于谁生产,谁分配,谁拥有,谁出租,谁工作—我们可以做出关于谁有权力和谁没有权力,以及关于谁会为自己做得好,谁会做得很差的推论。

We can say something intelligent, in other words, about the rhythms of economic life in that society, about the character of political conflict that might emerge, and even about the nature of ideas or ideologies that agents in that society will find compelling.

我们可以说一些聪明的东西,换句话说,关于社会中经济生活的节奏,可能出现的政治冲突的特征,甚至是社会中的积极参与者会发现的引人注目的思想或意识形态的本质。

What’s relevant for our purposes is that it is impossible to make this argument without being committed to some stable expectations about what humans are like across time and across space. At its essence, historical materialism is a set of claims about how an abstract human is likely to behave when she finds herself with or without certain resources and arrayed against other humans who are similarly or differently positioned.

与我们的目的相关的是,如果不致力于对人类在跨越时间和空间的情况下的某些稳定期望,就不可能做出这一论证。从本质上说,历史唯物主义是关于一个抽象的人类在发现自己有或没有某些资源时会如何表现并且与其他类似或不同位置的人排列在一起的主张。

If you take out the anchoring model of what humans are like in the abstract, if you reject any and all claims about human nature, the whole edifice comes crashing down. You lose the ability then to make sense of these core questions.

如果你在抽象中取出关于人类是怎样的的锚定模型,如果你拒绝任何和所有的关于人性的主张,那么整个大厦就会崩溃。你失去了理解这些核心问题的能力。

Anyone who wants to change society has to ask: why are some people poor? Why are other people rich? Why are some people powerful? Are other people powerless? How do we counter the power of the powerful? If you take out the anchoring model, human societies become nothing more than a blooming, buzzing, confusion of an infinite number of hierarchies, roles, ideas, beliefs, and rituals, etc.

任何想要改变社会的人都要问:为什么有些人穷困? 为什么其他人富有? 为什么有些人有权力? 其他人没有权力吗? 我们如何抵抗掌权者的权力? 如果你拿出锚定模型,那么人类社会就变成了无数盛开,嗡嗡,混乱的层次,角色,观念,信仰和仪式等元素。

People on the Left are very fond (and rightly so) of quoting thesis eleven from Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach”: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it.” Thesis ten-and-three-quarters is definitely, “If you want to change the world, you have to make sense of it first.” The Blank Slate Thesis makes that impossible.

左派们非常喜欢(并且也是正确地)从马克思的“费尔巴哈提纲”中引用提纲第11篇:“哲学家只解释世界,而关键在于改变世界。”提纲的十分之四和四分之三肯定的是,“如果你想要改变这个世界,你必须首先理解它。”白板理论使这变得不可能。

The Political Problem

政治问题

So we’ve had a moral problem, and we’ve had an analytical problem. The third problem is a political problem: the Blank Slate Thesis leads to ruinous political analysis. It makes it very difficult for socialists to apprehend the tasks ahead of us in a non-socialist world. It leads to bad diagnoses and bad strategy.

所以我们有道德问题,而且我们有分析问题。 第三个问题是政治问题:白板理论通向毁灭性的政治分析。这使得社会主义者很难理解我们在非社会主义世界中面临的任务。 它会导致糟糕的诊断和糟糕的策略。

What do I mean by this? Why would our position on human nature bear on our ability to win people to our politics? Let’s start with some sobering reminders first. We live in a society in which our politics are not mainstream.

这是什么意思? 为什么我们对人性的立场会影响我们赢得人们认可我们的政策的能力? 让我们先从一些清醒的提醒开始。我们生活在一个我们的政策不占主流的社会中。

It’s not a surprise. The enormous growth of socialist groups after Bernie Sanders, the widespread support for something like socialism among a younger generation at the polls — I don’t want to deny any of that.

这并不奇怪。Bernie Sanders之后社会主义组织的巨大增长,民意调查中年轻一代对社会主义的广泛支持—我并不想否认这些。

But at the same time, we cannot forget that we’re still small, we’re still weak, and we’re still operating on the margins of this society.

但与此同时,我们不能忘记,我们仍然很小,我们仍然很弱,而且我们仍然行动在这个社会的边缘。

When a small, weak, and marginal group looks out from its minoritarian vantage point onto society, there are two ways in which it tends to make sense of its own marginality. The first one is to believe that people aren’t signing up because they fail to see what we see. They don’t get it.

当一个小的,弱的,边缘的组织从其少数主义的视角看待社会时,有两种方式可以使自己的边缘感变得有意义。第一个是相信人们没有参与,因为他们没有看到我们所看到的。 他们没有明白过来。

On the Left, enormous energy goes into these kinds of explanations. People aren’t with us because they aren’t woke. And why aren’t they woke? Because they’re bigoted, they’re stupid, they’re ignorant, they’re sexist, they’re racist, they’re nationalist, they’re xenophobes, and on and on.

在左派这边,巨大的能量进入了这类解释中。 人们不和我们在一起因为他们没有清醒过来。 他们为什么没有清醒? 因为他们是顽固的,他们是愚蠢的,他们是无知的,他们是性别歧视者,他们是种族主义者,他们是民族主义者,他们是仇外者,以及其他的。

That’s one way to make sense of why people don’t get it. And if I convince you of nothing else, please let me convince you that this is the wrong way.

这是解释人们为什么不能明白过来它的一种方法。 如果我不让你信服,请让我说服你,这是错误的方法。

The correct way, the better way, to make sense of our marginality is to invert this view — to flip it on its head entirely. We are few and they are not with us, not because they’ve failed to understand what we see, but because we’ve failed to understand what they have seen. We have failed to put ourselves in their shoes and take a walk through the world as they’ve experienced it.

正确的方法,更好的方法,来理解我们的边缘性是倒转这种观点——完全翻转它的头。我们是少数,他们没有和我们在一起,不是因为他们不理解我们所看到的,而是因为我们无法理解他们所看到的。 我们没有穿上自己的鞋子,然后走遍他们经历过的世界。

What do I mean by this? Let’s take the enormous orange-haired elephant in the room. How are we to understand a white worker in West Virginia voting for a billionaire windbag? Or how 53 percent of white women could vote for the same man? Good answers to these sorts of political questions are distinguished from bad answers by one simple fact: they take seriously what it means to have lived the life of the person whose actions or beliefs you’re trying to explain.

这是什么意思? 我们来看看房间里巨大的橙色大象。 我们如何理解西弗吉尼亚州一位投票给废话连天的亿万富翁的白人工人? 或者53%的白人女性如何投票给同一个男人? 对这些政治问题的好的答案与的不良答案用一个简单的事实就能区分开来:他们认真对待了那些过着你正试图解释的行为或信仰的人的生活所意味着的东西。

In other words, a good political answer is one which puts you in the shoes of the person you’re trying to account for.

换句话说,一个好的政治答案就是让你穿上你想要解释的人的鞋子。

What does it mean to put yourself in their shoes? This is the critical point. It means remembering that a Trump voter is a human being animated by the same kinds of interests that animate you. She cares about her livelihood, her dignity, her autonomy, her family in much the same way that you do.

把自己穿上他们的鞋子是什么意思? 这是关键点。 这意味着要记住特朗普的选民是一个受到被激励你的利益同样激励的人类。她关心的是她的生计,尊严,自主权,她的家庭,就像你一样。

Your explanation and practice, in other words, should past a simple litmus test: could it explain why I would have voted Trump, had I been born her?

换句话说,你的解释和实践应该通过一个简单的试金石:它能否解释为什么我会投票给特朗普,如果我出生时成为了她?

If we fail to do this, we will find the tasks ahead of us impossible. Organizing is not really the task of preaching to the woke, but in large part, the task of awakening the not-yet-woke.

如果我们不这样做,我们就会发现我们面临的任务是不可能的。进行组织并不是一个向觉醒者宣传就能完成的任务,而是在很大程度上通过唤醒未觉醒者才能完成的任务。

But if you can’t put yourself in their shoes, you will invariably find yourself talking down to them. Rather than meeting them where they are at, you will find yourself livid that they are not yet where you are. And that will lead to a lot of vigorous, condescending, and elitist finger-wagging.

但如果你不能穿上他们的鞋子,你总会发现自己正在居高临下的和他们说话。 比起在他们所在的地方见到他们,你会发现自己不在他们所在的地方。这将导致许多猛烈的,居高临下的和精英主义的手指摇摆。

So this is the third problem, the political problem: the Blank Slate Thesis encourages you to forget that people are always meaningfully animated by certain unshakeable concerns. If we’re going to win people to our side, we have to take these concerns seriously. We have to take their human nature seriously.

所以这是第三个问题,政治问题:白板理论鼓励你忘记人们总是因某些不可动摇的问题而有意义地被激励。 如果我们要赢得人们的支持,我们必须认真对待这些问题。 我们必须认真对待他们的人性。

Human Nature in Capitalism

资本主义下的人性

If you commit to the Blank Slate Thesis, as a socialist you face three kinds of problems. A moral problem, an analytical problem, and a political problem. So don’t do it. Don’t let your friends do it and don’t do it yourself.

如果你认可白板理论,作为一个社会主义者,你面临三类问题。 道德问题,分析问题和政治问题。 所以不要这么做。不要让你的朋友这么做,不要自己这么做。

But so far I haven’t made an argument on how to respond to our annoying cousin — just how not to respond. In fact, I’ve conceded that our cousin, our family free-marketeer, is right on two points. He’s right to argue that there’s a universal human nature, and he’s right to note that this means that people everywhere care about themselves and the interests of their loved ones.

但到目前为止,我还没有就如何回应我们讨厌的堂兄的问题提出意见——只是如何不回应。 事实上,我已经承认,我们的堂兄,我们家中的自由市场鼓吹者,在两点上是正确的。 他认为存在一种普遍的人性是正确的,他也正确的指出这意味着世界各地的人都关心自己和所爱的人的利益。

Given these concessions to his argument, what distinguishes us as socialists from him? How should socialists respond? How do we defend the idea of a new society different from this one — a society in which people aren’t just out to maximize returns to themselves, a society which takes care of the weak, the vulnerable, the unfortunate?

鉴于对他的这一论点的这些让步,我们作为社会主义者与他的区别是什么? 社会主义者应该如何回应? 我们如何捍卫一个与这个社会不同的新社会的观念——一个人们不仅仅是为了让自己获得最大回报的社会,一个照顾弱者,弱势群体,和不幸者的社会?

To defend this vision against his, we have to make two clarifying arguments — one about this thing that we’re calling “human nature,” and one about how it expresses itself in social life.

为了捍卫这种反对他的观点,我们必须提出两个明确的论点—一个是关于我们称之为“人性”的事物,另一个关于它如何在社会生活中表达自己。

The major mistake made by our family free-marketeer is that he paints a flat, simplistic portrait of what human nature entails. So of course he’s partly correct. Humans everywhere care about themselves. They care about having enough to eat, they want to be cared for when sick, they care about having a roof over our heads. We also care deeply about certain intangibles. Our autonomy, our dignity, and maybe even some unsavory things about ourselves — what people think of us, our standing in the eyes of our peers.

我们家中的自由市场鼓吹者的主要错误在于他描绘了一幅关于人性的平面的,简化的画面。 所以他当然是部分正确的。 人类在所有地方都关心他们自己。 他们关心有足够的食物,他们想要在生病时得到照顾,他们关心的是在我们头上有一个屋顶。我们也非常关心某些无形资产。 我们的自主权,尊严,甚至可能是关于我们自己的一些令人讨厌的事情—人们对我们的看法,我们在同龄人眼中的地位。

But our antagonist’s view of human nature is one in which we care only about these things, in which we only care about maximizing returns from the world to ourselves.

但是我们的敌人对人性的看法是我们只关心这些,我们只关心将世界到自己的回报最大化。

This is the bourgeois view. The abstract human is basically like a two-year-old on an airplane. Nobody else matters. And if this were true, our project would be doomed. Out of toddlers on an airplane, I think you’d probably be able to build a world of an Ayn Rand novel, but you wouldn’t be able to build socialism.

这是资产阶级的观点。 这个抽象的人基本上就像飞机上的两岁小孩。 不在乎其他任何人。如果这是真的,我们的计划将注定失败。在飞机上的幼儿们,我想你可能能够建立一个Ayn Rand小说中的世界,但你将无法建立社会主义。

But the bourgeois view is only partly correct. Humans are capable of many things other than simple selfishness. We’re capable of caring for others, we’re capable of empathy and compassion, we have the capacity to distinguish fairness from unfairness, and the capacity to hold ourselves to those standards.

但这一资产阶级的观点只是部分正确。除了简单的自私之外,人类还能做很多事情。 我们有能力照顾他人,我们有同情心和恻隐之心,我们有能力区分公平与不公平,以及有能力坚持这些标准。

The bourgeois view inflates our selfish drives and ignores these other qualities. Socialists do not have to do the same. Human nature is not infinitely plastic. Its contain a variety of drives and capacities — some inner demons and some better angels, to quote Steven Pinker.

这一资产阶级的观点夸大了我们自私的动力,忽视了其他这些品质。社会主义者们不必这样做。 人性不是无限可塑的。 引用Steven Pinker:它包含各种驱动和能力—一些内部的恶魔和一些更好的天使。

Here’s the second point. Notice what our antagonist’s argument entailed: that whatever the character of the society in which humans find themselves, their underlying selfishness, their underlying competitiveness, is going to eat away at social structures until those social structures have been rendered irrelevant or totally transformed. Biology overpowers society.

这是第二点。 注意我们的敌人的论证所包含的内容:无论人类发现自己时所处的社会特征是怎样的,他们潜在的自私,潜在的竞争力,都会蚕食社会结构,直到这些社会结构变得无关紧要或完全转变为止。生物学压倒了社会。

In response, it is tempting to argue that human nature does not matter at all. But this is wrong, for the three reasons already outlined. So what should we say, in response? We should argue that human nature is always relevant, but never decisive.

作为回应,人们很容易认为人性根本不重要。 但由于已经概述的三个原因,这是错误的。 那么我们该怎么回应呢? 我们应该争辩说,人性总是相关的,但从不起决定作用。

Think about the way in which society is organized. What do people have to do to reproduce themselves? What do they have to do to other people in order to reproduce themselves? These facts exercise selectional pressures on the set of drives that constitute our human nature. The socialist wager, in a sentence, is that a better society would encourage our better tendencies.

想想社会组织的方式。 人们需要做些什么来再生产自己? 为了再生产自己,他们必须对其他人做些什么? 这些事实对构成我们人性的驱动集合施加了选择压力。 一句话,社会主义的保证是一个更好的社会会鼓励我们的更好的倾向。

This is not to argue that the other aspects of our nature can ever be ignored. A better society will no doubt have to respect certain limits. It will have to satisfy our needs. It will have to grant us our desires for freedom, for autonomy, our need to be respected. Socialism will most definitely fail if it requires us to be altruistic or saints, because the vast majority of people are not built to be either of those things.

这并不是说我们的人性的其他方面可以被忽视。 一个更好的社会无疑必须尊重某些限制。 它必须满足我们的需求。 它必须给予我们对自由,自治和我们需要得到尊重的渴望。 如果社会主义要求我们是利他主义者或圣人,那么社会主义肯定会失败,因为绝大多数人并不会成为他们。

Whatever else socialism might mean, it cannot mean a society in which people are called upon to systemically sacrifice themselves for some ideal, be it the fatherland, the working class, the world revolution, the supreme leader. That road leads straight to Pyongyang.

无论社会主义可能意味着什么,它都不能指一个人们被要求为一些理想而系统地牺牲自己的社会,无论是祖国,工人阶级,世界革命,还是最高领导人。 那条路直接通往平壤。

However, a society which caters to everyone’s universal needs, which helps everyone flourish — this is a society that would encourage and nurture the good that lies inside all of us.

然而,一个满足每个人的普遍需求的社会,这有助于每个人都蓬勃发展—这个社会将鼓励和培育存在于我们所有人内部的利益。

It is true in some important sense that our free-marketeer cousin knows only capitalist men and women. Socialist men and women would be different. They would still care about themselves and their needs, but a better society would also encourage them to take seriously the interests and needs of others.

的确,在某种重要意义上,我们的自由市场鼓吹者堂兄只知道资本主义的男女。 社会主义的男女会有所不同。 他们仍然会关心自己和他们的需求,但一个更好的社会也会鼓励他们认真对待他人的利益和需求。

Human Nature in Socialism

社会主义下的人性

How would it do this? We can only speculate, of course. But I can think of two ways. First, a society which meets everyone’s needs is a society in which there would be less to quarrel about. Less reason for aggression, less reason for violence, less reason for predation. Compare the person you are when you’re sharing a box of cookies with your brother or sister, to the person you are when you’re sharing one cookie.

社会主义会如何做到这些? 当然,我们只能推测。 但我可以想到两种方式。 首先,满足每个人需求的社会是一个不会争吵的社会。 减少侵略的理由,减少暴力的理由,减少掠夺的理由。 将与兄弟或姐妹共享一盒曲奇饼时的你与共享一个曲奇饼时的你进行比较。

The second point is that socialism would also be a much more egalitarian society. People would be each other’s equals — not subordinates or superiors.

第二点是,社会主义也将是一个更加平等的社会。 人们彼此是平等的—不是下属或上级。

I’m sure many of you have heard of the Stanford prison experiment, which illustrated that hierarchies can make monsters out of ordinary humans. Well, the absence of these hierarchies should make it easier to bid farewell to the monsters inside us.

我相信你们中的许多人都听说过斯坦福大学的监狱实验,这个实验表明,等级制度可以使怪物冲出普通人类的体内。 嗯,缺少这些等级制度应该可以更容易让我们告别我们内部的怪物。

In a more developed, and more egalitarian society, better humans will flourish. Socialists one, libertarian cousin zero.

在一个更发达,更平等的社会中,更好的人类将蓬勃发展。 社会主义者一,自由主义堂兄零。

You have perhaps been tempted in the past to make the argument that there is no such thing as a human nature. That temptation is understandable — I’ve been there. But it’s wrong for three reasons: a moral reason, for an analytical reason, and for a political reason.

在过去,你或许曾经受过诱惑,认为没有人性这种东西。 这种诱惑是可以理解的——我曾经也是如此。 但这是错的,因为有三个原因:道德原因,分析原因和政治原因。

Socialists do believe — we must believe — that there is something called human nature. In fact, I believe that you believe it, whether or not you believe that you believe it. But we make two arguments that distinguish us from our bourgeois antagonists.

社会主义者确实相信—我们必须相信—有一种叫做人性的东西存在。 事实上,我相信你相信它,不管你是否相信你相信它。 但我们提出了两个将我们与我们的资产阶级敌人区别开来的论点。

First, human nature comprises not just an interest in ourselves, but also compassion, empathy, capacity for reflection, capacity to be moral. And second, the way in which society is organized can amplify these drives and downplay others.

首先,人性不仅包括在乎自己的利益,还包括同情心,同理心,反思的能力,拥有道德的能力。 其次,社会组织的方式可以增大这些驱动力并减少其他驱动力。

All this means that another world is definitely possible. Don’t let the fools get you down and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

这一切意味着另一个世界绝对是可能的。 不要让傻瓜们使你失望,不要让任何人告诉你相反的东西。

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/04/human-nature-socialism-capitalism-greed-morality-needs/

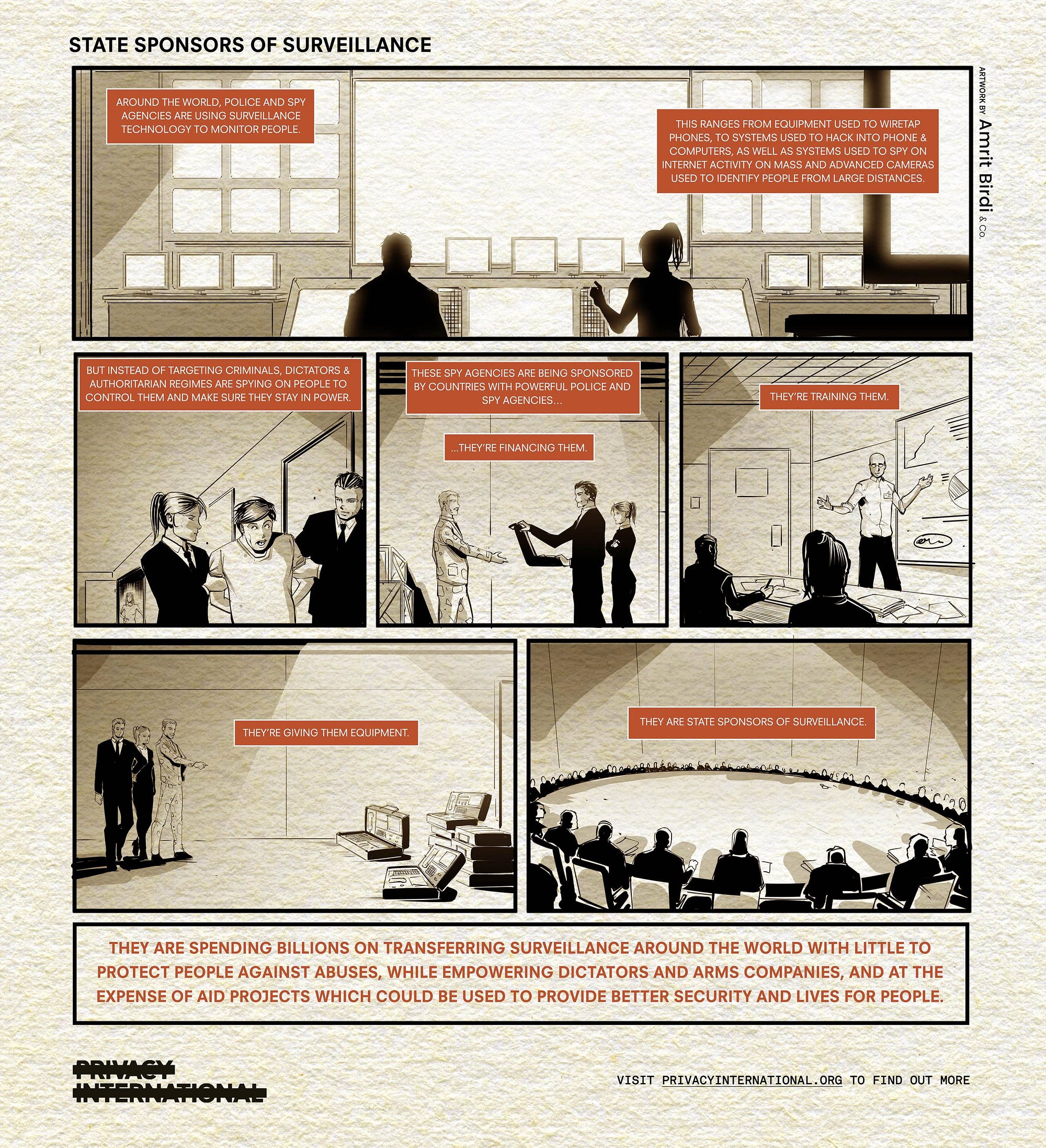

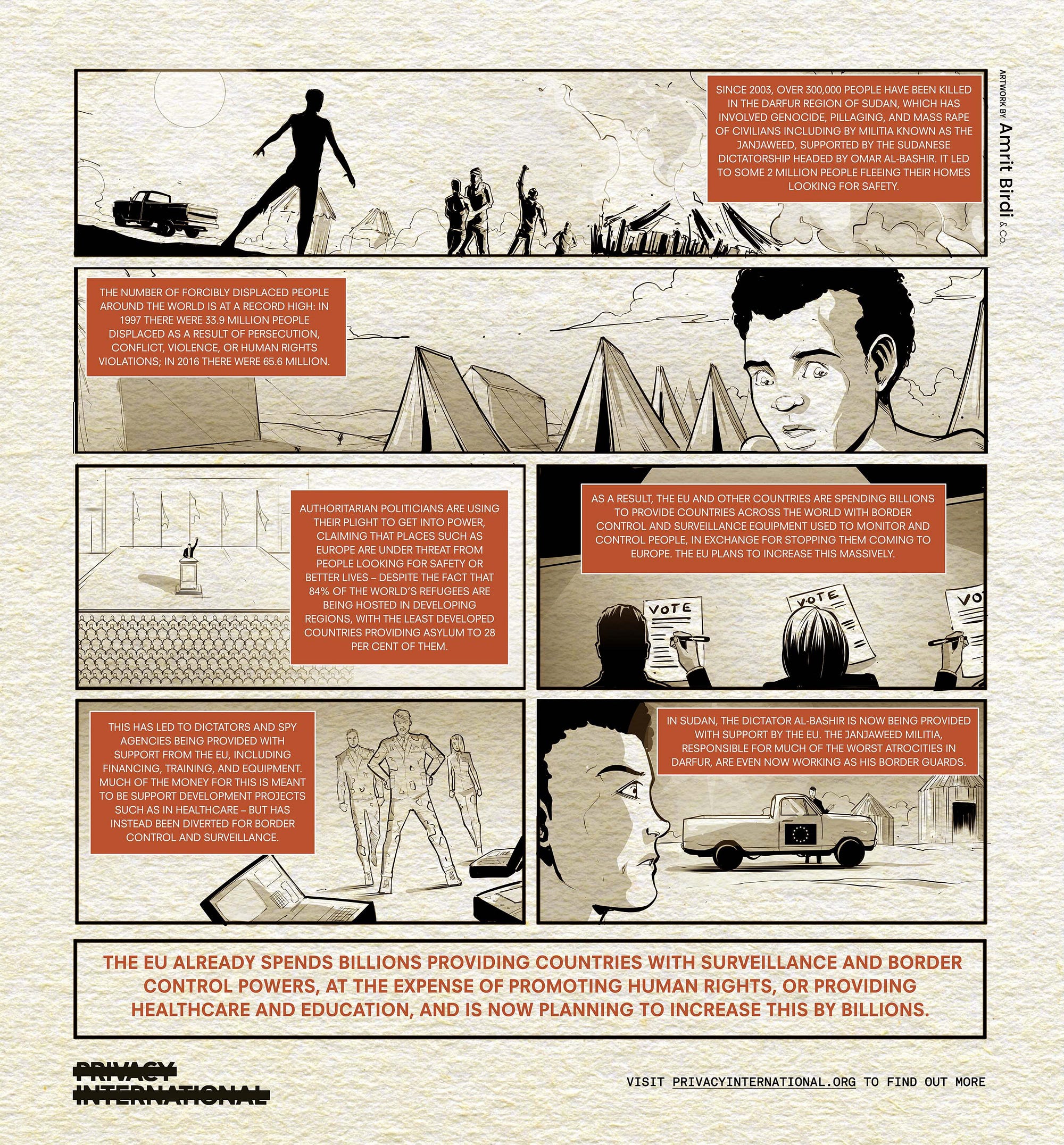

监控能力正在全球迅速蔓延。所有期待权力稳固的政府、以及热衷于出售监视技术能力的行业,在互联网构建的圆形大监狱中感受着异常的兴奋。监视正在作为解决一切政治经济社会等棘手问题的最有效方案。作为人权捍卫者,我们需要

监控能力正在全球迅速蔓延。所有期待权力稳固的政府、以及热衷于出售监视技术能力的行业,在互联网构建的圆形大监狱中感受着异常的兴奋。监视正在作为解决一切政治经济社会等棘手问题的最有效方案。作为人权捍卫者,我们需要